Introduction:

Oral sub mucous fibrosis (OSMF) is an insidious, chronic, resistant disease which may involve the submucosa of any part of the oral cavity and may extend upto pharynx and esophagus. The disease which was considered primarily a disease prevailing in the southern Asia and southern Asian immigrants to other parts of the world (1,2) has now gained considerable attention world-wide.

The etiology of this crippling disease is complex even though the actual mechanism is obscure. The condition has a multifactorial origin but is commonly associated with chewing of areca nut (betel nut) habitually (3).

The disease has a spectrum of presentations ranging from, excessive salivation, burning sensation, absent gustatory sensation and limitation of mouth opening leading to difficulty in chewing, swallowing, articulation and poor oral hygiene and its complications. It has been associated with an increased risk of malignancy and hence is considered as a pre-malignant condition (4).

The main aim in the treatment of submucous fibrosis is to relieve the symptoms and improve the oral opening. The non surgical management of such a patient includes discontinuation of the habit, avoidance of spicy foods, medicinal measures like local steroids, placental extracts, hyaluronidase injections singly or in combination and oral anti-oxidant supplements along with jaw opening exercises. Surgical measures attempting at excision of fibrous bands, coverage of resultant defects with skin grafts, collagen or other dressing materials, buccal pad of fat, local flaps, vascularised flaps, with or without coronoidectomy and post-operative active jaw physiotherapy have been documented.

History:

0SMF has been well established in Indian medical literature since the time of Sushruta-- a renowned Indian physician who lived in the era 600 B.C and was termed as 'Vidari'. It was first described in the modern literature by Schwartz in 1952 who coined the term atrophica idiopathica mucosa oris to describe an oral fibrosing disease, he discovered in 5 Indian women from Kenya(5). Joshi subsequently coined the termed oral submucous fibrosis (OSMF) for the condition in 1953(6).

This condition has been referred to under a number of names, diffuse oral submucous fibrosis(7), idiopathica scleroderma of the mouth(8), idiopathic palatal fibrosis(9)

Prevalence:

Global estimates from 1996 indicate that about 2.5 million people have OSMF (10). However, results from studies conducted in 2002 (11) indicate that more than 5 million people in India have OSF (0.5 percent of the Indian population). In addition, it is estimated that up to 20 percent of the world's population consumes betel nut in some form,(12) so the prevalence of OSMF probably is higher than that noted in the published literature.

The rate varies from 0.2-2.3% in males and 1.2-4.57% in females in Indian communities.(13) Oral submucous fibrosis is widely prevalent in all age groups and across all socioeconomic strata in India. The occurrence of this condition in children is extremely rare. Youngest case reported in the literature was a 4-year-old girl (14). A case of OSMF in a 12 year old girl was reported in 1993 and the etiology was traced to be the habit of chewing roasted areca nuts (15). Another case of a 11 year old girl was reported in 2001 highlighting the link between oral submucous fibrosis and the regular use of areca-nut (paan) and the newer trans-cultural oral tobacco products (16)

A sharp increase in the incidence of oral submucous fibrosis was noted after pan masala came into the market, and the incidence continues to increase. Migration of endemic betel quid chewers has also made oral submucous fibrosis a public health issue in many parts of the world, including the United Kingdom, South Africa, and many Southeast Asian countries.(17)

Etiopathogenesis:

Although various factors have been implicated in the development of oral submucous fibrosis, the exact role of any one of these in the development, severity and extent of the disease is not clear, as the disease may still occur if none of these is present.

When the disease was first described in 1952, it was classified as an idiopathic disorder (5).

Earlier workers correlated it with hypersensitivity to capsaicin (Capsicum annum and Capsicum fructescens-- an active ingredient in chilies -- secondary to chronic iron and/or vitamin B complex deficiencies; or exposure to cashew kernel oil(4,18). Ramanathan summarized the evidence of OSMF being a mucosal change secondary to chronic iron and/or Vitamin B Complex deficiency. He suggested that the disease is an Asian analogue of sideropenic dysphagia(19).

Currently, the habit of chewing areca nuts (the fruit of Areca catechu plant) is recognized as the most important etiologic agent in the pathogenesis of this condition. A number of epidemiological surveys, case-series reports, large sized cross sectional surveys, case-control studies, cohort and intervention studies provide over whelming evidence that areca nut is the main aetiological factor for OSMF (7, 20-22). Four alkaloids have been conclusively identified in biochemical studies, arecoline, arecaidine, guvacine, guvacoline, of which arecoline is the main agent. The alkaloid component of the betel nut stimulates the inflammatory process (20). An initial epithelial inflammation is followed by fibro-elastic changes in the lamina propria (20,23). Epithelial atrophy and collagen deposition result in the formation of dense fibrotic bands. Overactivity during chewing causes ischaemic changes. Subsequent fibrosis and scarring in the masticatory muscles contribute further to fibrotic band formation and trismus. These bands are visible in the palate, buccal and labial areas and, in later stages, in the pharyngeal and oesophageal areas. In vitro studies on human fibroblasts using areca extracts or chemically purified arecoline support the theory of fibroblastic proliferation and increased collagen formation that is also demonstrable histologically in human OSMF tissues (24). The role of areca alkaloids, copper in fibroblast proliferation and increased collagen synthesis, stabilization of collagen structure by tannins and fibrogenic cytokines, genetic polymorphisms predisposing to OSMF, role of the collagen related genes CoL1A2, COL3A1, CoL6A1, COL6A3 and COL7A1 have been discussed by W.M. Tilakaratne et al(25).

A possible autoimmune basis to the disease with demonstration of various auto-antibodies and an association with specific HLA antigens A10, DR3, DR7, and probably B7, along with haplophytic pairs A10/DR3, B8/DR3, and A10/88, has been found (26). These pairs, together with the presence of autoantibodies and chronic inflammation of the oral mucosa, have been suggested as an autoimmune basis of oral submucous fibrosis.

Clinical Features

The most frequently affected locations in oral submucous fibrosis are the buccal mucosa and the retromolar areas. It also commonly involves the soft palate, palatal fauces, uvula, tongue, and labial mucosa. It is generally believed that oral submucous fibrosis originates from the posterior part of the oral cavity and subsequently involves the anterior locations(27). A study on the regional variations of this condition pointed out that such an observation would depend on whether the areca nut juice and the quid are swallowed or spat out(28).

It manifests as a burning sensation in the mouth, intolerance to eating hot and spicy foods, blanching and stiffness of the oral mucosa, trismus, vesiculation, excessive salivation, ulceration, pigmentation change, recurrent stomatitis, defective gustatory sensation, dryness of the mouth , gradual stiffening and reduced mobility of the soft palate and tongue leading to difficulty in swallowing and hyper nasality of voice, hoarseness of voice (with laryngeal involvement) and occasionally, mild hearing loss due to blockage of Eustachian tube (29).

The precancerous nature of oral submucous fibrosis has been observed with development of slowly growing squamous cell carcinoma in one-third of oral submucous fibrosis patients(30). In southern India, 40% of oral cancer patients had oral submucous fibrosis(31). A 7.6% incidence of oral cancer in oral submucous fibrosis patients has been reported in a median 10-year follow-up period (11). Pindborg et al. summarized the criteria in support of the precancerous nature of the disease as higher prevalence of leukoplakia among oral submucous fibrosis patients, high frequency of epithelial dysplasia, concurrent finding of oral submucous fibrosis in oral cancer patients, and histologic diagnosis of carcinoma without the clinical suspicion of it(32).

The malignant transformation rate for OSF is 7 to 30 percent.(1,2,33)

The characteristic histologic features of OSMF consist of, atrophic epithelium often keratinized, generally without rete ridges, and in advanced cases it may be ribbon-like with juxtaepithelial hyalinization and collagen of varying density(31).

Staging:

Pindborg et al described 4 consecutive stages of oral submucous fibrosis based on histologic findings: very early stage, early stage, moderately advanced stage, and advanced stage(34).

Khanna and Andrade in 1995 developed a classification system for the surgical management of trismus(35).

Group I: Very early stage without mouth opening limitations with an inter-incisal distance of greater than 35 mm.

Group II: Early stage with an inter-incisal distance of 26-35 mm.

Group III: Moderately advanced cases with an inter-incisal distance of 15-25 mm. Fibrotic bands are visible at the soft palate, and pterygomandibular raphe and anterior pillars of fauces.

Group IVA: Advanced stage: Trismus is severe, with an inter-incisal distance of less than 15 mm and extensive fibrosis of the oral mucosa.

Group IVB: Disease is most advanced, with premalignant and malignant changes throughout the mucosa

Divya Mehrotra et al suggested a clinical grading of the disease and treatment methods as (27):

Grade I: stomatitis and burning sensation in the buccal mucosa with no detection of fibres. Suggested treatment for this group is abstinence from habit and medicinal management.

Grade II: symptoms of grade I, palpable fibrous bands, involvement of soft palate, and maximum mouth opening 26-35 mm. Suggested treatment: abstinence from habit and medicinal management.

Grade III: symptoms of grade II, blanched oral mucosa, involvement of tongue, and maximal mouth opening 6-25 mm. Suggested treatment: abstinence from habit and surgical management.

Grade IV: symptoms of grade III, fibrosis of lips, and mouth opening ?5 mm. Suggested treatment: abstinence from habit and surgical management.

S. M. Haider et al gave the following staging system(36):

Clinical and Functional Staging

Clinical Stage

1. Faucial bands only

2. Faucial and buccal bands

3. Faucial, buccal, and labial bands

Functional Stage

A Mouth opening ? 20 mm

B Mouth opening 11-19 mm

C Mouth opening ?10 mm

Management

The management of an OSMF patient depends on the degree of clinical involvement. It comprises of: discontinuation of areca-nut related habit, nutritional support and anti-oxidants, physiotherapy, immunomodulatory drugs(steroids) for local/systemic application, intra-lesional injections of steroids, hyaluronidase, human placental extracts etc, either singly or in combination for early/milder form of disease and surgical measures for advanced cases with post-operative nutritional support and anti-oxidants alongwith active physiotherapy to prevent contracture at the surgical site and recurrence. It is very essential to follow these patients closely in order to prevent recurrence and to detect any developing malignancy at its earliest so as to manage this untoward and most common eventuality.

Medical Care

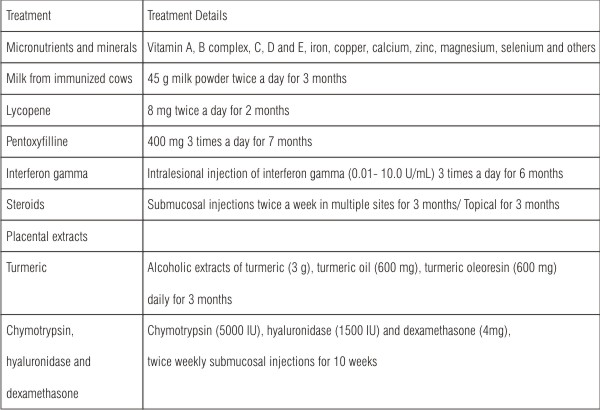

Medical treatment is symptomatic and predominantly aimed at improving mouth movements. The medical management has been summarized in the following table given by Auluck et al(37)

Surgical Care

Surgical treatment is indicated in patients with severe trismus and/or biopsy results revealing dysplastic or neoplastic changes. Surgical modalities that have been used include the following:

| Table 1: Treatment modality for OSF (Auluck et al., 2008).

|

Simple excision of the fibrous bands, excision of bands with myotomy with or without coronoidectomy, coverage of the raw area with skin grafts, fresh amnion, collagen membrane, buccal pad of fat, local flaps or vascularised free flaps, followed by active post-operative jaw physiotherapy with anti-oxidants and proper nutrition and regular follow-ups to ensure maintenance of oral opening and early detection of malignant changes if any.

Use of lasers for band excision also has been documented.

Coverage of the area with fibrin glue or Absorbable Atelocollagen also is being tried at various institutes.

Discussion:

Oral sub mucous fibrosis is a chronic, progressive, debilitating disease, which most commonly presents with burning sensation, intolerance to hot and spicy foods, difficulty in mouth opening with poor oral hygiene and its complications. OSMF most commonly affects the buccal mucosa In addition, there may be involvement of the retromolar areas, fauces, palate, tongue, pharynx and esophagus. The condition is sometimes preceded by and/or associated with vesicle formation, but always associated with a juxtaepithelial inflammatory reaction followed by a fibroelastic change of the lamina propria with epithelial atrophy, leading to stiffness of the oral mucosa and causing trismus and inability to eat (33). The underlying muscles and the muscles of mastication can also be affected. However, a more serious complication of this disease is the risk of the development of oral carcinoma (20). The precancerous nature of oral submucous fibrosis has been observed with development of slowly growing squamous cell carcinoma in one-third of oral submucous fibrosis patients (27). Oral leukoplakia occurs with a high incidence among patients with submucous fibrosis. According to Pindborg's report on OSMF in India, leukoplakia occurred in 55% cases (32).

The aim of treatment for this condition is to provide good release of fibrosis and provide long term results in terms of maintainence of mouth opening and to detect any developing malignant change at its earliest.

Different treatment methods for oral submucous fibrosis have been discussed.

Administration of vitamin B-complex may relieve glossitis and cheilosis in OSMF patients (38). A peripheral vasodilator, such as buflomedial hydrochloride, affects the tissues in diffuse fibrosis to a noticeable degree by relief of the local ischemic effect (39).

Pentoxifylline is a tri-substituted methylxanthine derivative, which increases red cell deformability, leukocyte chemotaxis, antithrombin and anti- plasmin activities, and more importantly to the present context, its fibrinolytic activity. Pentoxifylline decreases red cell and platelet aggregation, granulocyte adhesion, fibrinogen levels, and whole blood viscosity (40). Recent work has delineated pentoxifylline's ability to decrease production of tumor necrosis factor alpha and reduce some of the systemic toxicities mediated by interleukin-2 (41). The anti inflammatory and immunomodulatory actions led to subjective improvement in clinical outcome recorded in a study by R Rajendran et al (42).

Lycopene: A number of studies have proven that the management of premalignant lesions should include antioxidants along with the cessation of the habit. Lycopene is a powerful antioxidant obtained from tomatoes. It has been shown to have several potent anti-carcinogenic and antioxidant properties and has demonstrated profound benefits in precancerous lesions such as leukoplakia (43) It has been found to inhibit hepatic fibrosis in rats as well as human fibroblast activity in vitro suggesting its possible role in the management of oral submucous fibrosis(44). Newer studies highlight the benefit of this oral nutritional supplement at a daily dose of 16 mg. Mouth opening in 2 treatment arms (40 patients total) was statistically improved in patients with oral submucous fibrosis. This effect was slightly enhanced with the injection of intralesional betamethasone (two 1-mL ampoules of 4 mg each) twice weekly, but the onset of effect was slightly delayed.(45)

Steroids: In patients with moderate oral submucous fibrosis, weekly submucosal intralesional injections or topical application of steroids may help to prevent further damage. Steroid ointment applied topically helps in cases with ulcers and painful oral mucosa. Its therapeutic effects were mainly anti-inflammatory and appeared to have a direct healing action (46) Steroids are well known to act as immunosuppressive agents for prevention or suppression of the fibroproductive inflammation found in OSMF lesions, thus ameliorating this fibro-collagenous condition (47) Placental extracts: The rationale for using placental extract in patients with oral submucous fibrosis derives from its proposed anti-inflammatory effect(48), hence, preventing or inhibiting mucosal damage. Cessation of areca nut chewing and submucosal administration of aqueous extract of healthy human placental extract (Placentrex) has shown marked improvement of the condition.(15)

Hyaluronidase: The use of topical hyaluronidase has been shown to improve symptoms more quickly than steroids alone. Hyaluronidase can also be added to intralesional steroid preparations. The combination of steroids and topical hyaluronidase shows better long-term results than either agent used alone.(49) Hyaluronidase degrades the hyaluronic acid matrix, actively promoting lysis of the fibrinous coagulum as well as activating specific plasmatic mechanisms (49,44). Therefore, relief of trismus may be expected through softening and diminishing of fibrous tissue.

IFN-gamma: This plays a role in the treatment of patients with oral submucous fibrosis because of its immunoregulatory effect. IFN-gamma is a known antifibrotic cytokine. IFN-gamma, through its effect of altering collagen synthesis, appears to be a key factor to the treatment of patients with oral submucous fibrosis, and intralesional injections of the cytokine may have a significant therapeutic effect on oral submucous fibrosis(50).

The surgical treatment involves excision of fibrous bands and forceful mouth opening resulting in a raw wound surface. Relapse is common complication that occurs after surgical release of the oral trismus caused by OSMF. Initially surgeons aimed at surgical elimination of the fibrotic bands which showed further scar formation and recurrence of trismus, to prevent which, they started using various inter positional graft materials (51,52).

Yeh carried out a surgical procedure of incising the mucosa down to the muscles from the angle of mouth to the anterior tonsillar pillar, taking care to prevent damage to the stoma of the parotid duct, followed by split skin grafting into the defect, with acceptable results (53).

Canniff et al. described the procedure of split thickness skin grafting after bilateral temporalis myotomy or coronoidectomy along with daily opening exercise and nocturnal props for a further 4 weeks (26). But the results with skin grafting have a high reoccurrence rate due to graft shrinkage(35,38,54). The other limitation of the split thickness skin graft is the morbidity associated with the donor site along with maintenance of mouth opening post operatively for 7 to 10 days which is the most unpleasant and uncomfortable experience for the patient(55) .

Collagen membrane is used as a biological dressing. Shobha Nataraj et al used collagen membrane composed of type I and type III bovine collagen (that is similar to human collagen), following excision of fibrotic bands to cover the raw areas during initial phase of healing and observed that collagen membrane had good adaptability to the surgical defect. Collagen when used to cover raw areas provides coverage for sensitive nerve endings thereby diminishing degree of pain. The adherence of collagen membrane is initially due to fibrin-collagen interaction & later due to fibro vascular in-growth into the collagen. With time, it slowly undergoes collagenolysis and is eventually sloughed off. However, it resists masticatory forces for sufficient time, to allow granulation tissue to form. None of the cases in their study showed any adverse reaction to the collagen proving its safety as a biological dressing (55,56,57).

The value of amniotic membranes as dressings for partial-thickness burns has been demonstrated by Dino et al. and Colocho et al. There was no acute rejection and its application over partial-thickness defects provides for pain relief and re-epithelialization. In patients for whom deep defects were covered by fresh amnion grafts, the inter-incisal distance two years after surgical treatment decreased by 5-10 mm. Therefore, fresh amnion grafts would not appear to be effective in a single layer over deep buccal defects according to Lai DR et al(38)

Borle and Borle reported disappointing results with skin grafting to cover the raw area and used tongue flap to cover the defect (46) However, tongue flaps were found to be bulky and required additional surgery for detachment. Bilateral tongue flaps caused severe dysphagia and disarticulation along with the risk of postoperative aspiration(55). Restricted mobility of tongue was observed in the immediate postoperative phase, causing discomfort to the patient and difficulty in speech, which made it a less ideal choice(27)

Khanna and Andrade reported the incidence of shrinkage, contraction, and rejection of split skin graft as very high, owing to poor oral condition, with recurrence in 12 cases. Palatal island flap based on the greater palatine artery had been used to cover defect. This technique, accompanied with bilateral temporalis myotomy and coronoidectomy, was a highly effective surgical procedure (35) . However, use of island palatal flap has limitation such as its involvement with fibrosis and second molar tooth extraction required for flap to cover without tension (32, 60)

Bilateral palatal flaps leave a large raw area on palatal bones in palate (61).

The nasolabial flap is typically classified as an axial pattern flap based on angular artery. It can be based superiorly or inferiorly. Kavarana and Bhatena filled the defect after sectioning of fibrous bands with 2 inferiorly based nasolabial flaps, with division of the pedicle after 3 weeks, and observed average mouth opening of 2.5 cm, with acceptable external scars (62). Inferiorly based nasolabial flap is a reliable, economical option for the management of oral submucous fibrosis (63). The advantages of nasolabial flap include its close proximity to defect, easy closure of donor site & a well camouflaged scar. The technique is easy to master and defects as large as 6 to 7 cm can be closed. The postoperative extra-oral scars are hidden in the nasolabial fold. Minor complications include loss of the nasomaxillary crease and the creation of an edematous and bulky flap. A periosteal suture can however be used to recreate the crease. By trimming all of the fat from the flap, the bulkiness can be reduced (64). However, the nasolabial flaps cannot be extended adequately to cover the raw area, and they also cause facial scars and at times is hair bearing (27)

Yeh described the application of pedicled buccal fat pad after incision of fibrous bands and suggested that this was a very logical, convenient, and reliable technique for treatment of oral submucous fibrosis (53). The surgical procedure is easy, less time-consuming since the donor site is in close proximity to the posterior third of the buccal defect and can be accessed and mobilized through the same buccal incision, which was used to release the fibrosis, without causing any noticeable defect in the cheek or mouth. Improvement in the suppleness and elasticity of the buccal mucosa on clinical examination were noted(53,55), The graft begins to show signs of epithelization from 2nd week with mean value of 14.73 days, so does not necessitate coverage with a skin graft (52,55,65), Should it fail, the consequences are not serious, as other options are open. Buccal fat pad serves as a good substitute, because it provides excellent function without deteriorating the esthetics and the results obtained were sustained long term (27). Thus Lai DR et al considered this as the quickest and most efficient form of therapy for OSMF patients with severe trismus to ensure long-term improvement in mouth opening (38).

Mokal et al. advocated the use of vascularized temporal myofascial pedicled flap to bring in good blood supply to the area of affected muscle and mucosa to improve its function (61).

A total of five patients were treated with this technique and all of them showed good mouth opening in long term follow up. There was no donor site morbidity. The incision line is well hidden in the hair bearing area. Moreover, this technique releases strong muscles of mouth closure such as masseter from its origin and temporalis from its insertion. This procedure has its foundation on anatomical landmarks and physiological facts and is an effective method of treating oral sub mucous fibrosis (61)

Extraoral local flaps are limited by their extensibility to deeper parts of the defects. Free tissue transfer is hence the preferred choice. The radial forearm free flap has been widely accepted

because of its reliability, its thin, pliable and relatively hairless tissue characteristics and its long and sizable pedicle. It is one of the most popular flaps used in head and neck reconstruction. Wei FC et al have successfully applied this flap to reconstruct oral submucous fibrosis post-release defects (66). Most donor sites were closed primarily in their series to leave only linear scars, thus the two most common donor-site problems encountered for radial forearm flaps, donor-site function and cosmetic appearance were avoided. A bi-paddled radial forearm flap from a single donor site has been also used for reconstruction of bilateral buccal defects(67). However, the sacrifice of one of the two major vessels supplying to the hand on both sides is still a concern, with the potential risk of compromising the circulation to the digits, ranging from cold intolerance to gangrene change, especially in the smokers. Free flap reconstruction has proved effective for maintaining mouth opening after release of fibrosis. Two independent free flaps from separate donor sites, such as bilateral forearm flaps or bilateral anterolateral thigh (ALT) flaps, were traditionally required for reconstruction. The former option sacrifices one of the two major arteries in the forearm. Both the options are time consuming and required two donor sites. To eliminate these disadvantages, Jung-Ju Huang et al developed a technical modification that allows harvesting of two independent flaps from one ALT thigh based on one descending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery (d-LCFA). With the described technique, two teams can work simultaneously, the total operation time can be reduced and one donor site can be left un-operated, one donor thigh scar can be concealed more easily than bilateral donor sites scarring both forearms, the sacrifice of the d-LCFA is less critical than the sacrifice of the radial artery. However, since ALT flaps may be too bulky for oral mucosa reconstruction, flap-thinning procedures, either intra-operatively during flap transfer reconstruction or secondarily after surgery may be undertaken(68).

Omura and Mizoki used a newly developed collagen/silicone bi-layer membrane as a mucosal substitute and reported that postoperative course was unremarkable and that repair was effective. The membrane comprised an outer layer of silicone and inner layer of hydrothermal cross-linked composites of fibrillar and denatured collagen sponge. The membrane was placed on oral mucosal defects after removal of the outer silicone layer after 10-14 days(69).

Use of a KTP-532 laser release procedure was found to increase mouth opening range in 9 patients over a 12-month follow-up period in one study(70).

Fibrous bands encircle the lips, buccal mucosa, and faucial pillars. The constriction of the oral aperture is not only disfiguring but also limits access needed for surgery. FRAME et al used CO2 laser, rather than a scalpel or a technique involving multiple tiny incisions for surgical relief of the limited oral aperture, because the laser beam spontaneously sealed all blood vessels, allowing the surgeon perfect visibility and accuracy in excising the fibrous tissues time55. Furthermore, the laser excised wound heals with less contraction and scarring than wounds left by surgical excisions71. However, Lai DR et al38 considered it be practically impossible to excise all fibrous tissues in the oral cavity at one time.

Fibrin glue is a biological tissue adhesive based on the final stage of coagulation wherein. Thrombin acting on fibrinogen converts it into fibrin. Thus, it has two components, fibrinogen and thrombin obtained from patient's own blood. Use of the fibrin glue is simple, safe, cost effective, and rapid technique. Its use to cover the raw areas after excision of fibrous bands is being tried at various institutes.

Absorbable Atelocollagen Membrane is available as a sterile, pliable surgical porous scaffold agent made of highly purified type I atelocollagen derived from porcine skin. It is being used for coverage of the raw areas in non-healing and burn wounds. It shows minimal antigen reaction due to the elimination of telopeptides, is completely absorbable, highly bio-compatible and suitable for reconstruction of soft tissue. Its advantages include, bleeding control and stabilization of the blood clot, acceleration of the wound healing process, provides matrix for tissue ingrowths, can be cut to fit any size wound, soft and conformable to wound site, maintains integrity in moist state, leaves wound free of fiber. Its use in OSMF is being tried in many institutes and long term results are awaited.

Patients suffering from this incurable, chronic fibro-elastic scarring disease need to be fully informed. It is essential at the onset of treatment to avoid raising expectations. Treatment needs to be coupled with cessation of betel/tobacco quid chewing and active jaw physiotherapy in order to manage properly both early and advanced stages of OSMF(38). Patients should be closely followed up to monitor the inter-incisal distance and any developing suspicious lesion so that appropriate and timely treatment for the same may be initiated.

Conclusion:

Oral submucous fibrosis is one of the most poorly understood and unsatisfactorily treated diseases. The younger the age, the more rapid the progression of the disease. Because of the significant cancer risk among these patients, periodic biopsies of suspicious regions of the oral mucosa are essential for early detection and management of high-risk oral premalignant lesions and prevention of cancer. Dentists can play an important role in both the education of patients about the perils of chewing betel quid and in the early diagnosis of such high-risk premalignant lesions and cancer.

References

1. van Wyk CW, Grobler Rabie AF, Martell RW, Hammond MG.,HLA-antigens in oral submucous fibrosis. J Oral Pathol Med 1994;23:23-27.

2. Maresky LS, de Waal J, Pretorius S, van Zyl AW, Wolfaardt P., Epidemiology of oral precancer and cancer. S Afr Med J 1989;Suppl:18-20.

3. Pillai R, Balaram P, Reddiar KS. Pathogenesis of oral submucous fibrosis. Relationship to risk factors associated with oral cancer. Cancer 1992;69:2011-2020.

4. SirsatSM, KhanolkarVR. Submucous fibrosis of the palate in diet-preconditioned Wistar rats.The Saudi Dental Journal, Volume 1, Number 2,1989 Arch Pathol 1960;70:171-179.

5. Schwartz J. Atrophia idiopathica (tropica) mucosa oris. Demonstrated at the 11th International Dental Congress, London 1952.

6. Joshi SG: Submucousf ibrosis of the palate and pillars. Indian J Otolaryngol 4:1-4, 1953.

7. Lal D: Diffuse oral submucous fibrosis. J All India Dent Assoc 26:1-3, 14-15, 1953.

8. Su JP. Idiopathic scleroderma of the mouth. Report of three cases. Arch Otolaryngol 1954; 59:330-2.

9. Rao ABN. Idiopathic palatal fibrosis. BrJZSurg 1%2623; 50: 23-5.

10. Cox SC, Walker DM. Oral submucous fibrosis: a review. Aust Dent J 1996;41(5):294-299.

11. Chiu CJ, Chang ML, Chiang CP, Hahn LJ, Hsieh LL, Chen CJ. Interaction of collagen-related genes and susceptibility to betel quid-induced oral submucous fibrosis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2002;11(7):646-653.

12. Gupta PC, Warnakulasuriya S. Global epidemiology of areca nut usage. Addict Biol 2002;7(1):77-83.

13. Aziz SR. Oral submucous fibrosis: an unusual disease. J N J Dent Assoc. Spring 1997;68(2):17-9

14. Hayes PA: Oral submucous fibrosis in a 4-year-old girl. Oral Surg 59:475-78, 1985

15. Anil S, Beena VT. Oral submucous fibrosis in a 12-year-old girl: case report. Pediatr Dent. Mar-Apr 1993;15(2):120-2

16. Shah B, Lewis MA, Bedi R. Oral submucous fibrosis in an 11-year-old Bangladeshi girl living in the United Kingdom British Dental Journal,2001;191; 130 - 132

17. Paul RR, Mukherjee A, Dutta PK, et al. A novel wavelet neural network based pathological stage detection technique for an oral precancerous condition. J Clin Pathol. Sep 2005;58(9):932-8

18. Rajendran R, Anll S, Vijayakumar T: Risk of Oral Submucous Fibrosis (OSMF) Among the Factory Workers of Kerala, South India, Exposed to Cashew. Proc Int Con Primary Health Care 9-12, 1988, New Delhi.

19. Ramanathan K: Oral submucous fibrosis -- an alternative hypothesis as to its causes. Med J Malaysia 36:243-45, 1981.

20. Murti PR, Bhonsle RB, Gupta PC, Daftary DK, Pindborg JJ, Metha FS. Aetiology of oral submucous fibrosis with special reference to the role of areca nut chewing. J Oral Pathol Med 1995;24:145-52.

21. Sinor PN, Gupta PC, Murti PR, Bhonsle RB, Daftary DK, Mehta FS, et al. A case-control study of oral submucous fibrosis with special reference to the aetiologic role of areca nut. J Oral Pathol Med 1990;19:94-8.

22. Seedat HA, Van Wyk CW. Betel nut chewing and oral submucous fibrosis in Durban. S Afr Med J 1988;74:572-5.

23. Rajalalitha P, Vali S. Molecular pathogenesis of oral submucous fibrosis- a collagen metabolic disorder. J Oral Pathol Med 2005;34

24. Harvey W, Scutt A, Meghji S, Canniff P. Stimulation of human buccal mucosa fibroblasts in vitro by betel nut alkaloids. Arch Oral Biol 1986;31:45-9

25. Tilakaratne WM, Klinikowski MF, Saku T, Peters TJ, Warnakulasuriya S. Oral submucous fibrosis: review on aetiology and pathogenesis. Oral Oncol. Jul 2006;42(6):561-8.

26. Caniff JP, Harry W, Harris M. Oral submucous fibrosis: its pathogenesis and management. Br Dent J 1986;160;429-34.

27. Divya Mehrotra, R. Pradhan, Shalini Gupta: Retrospective comparison of surgical treatment modalities in 100 patients with oral submucous fibrosis, Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2009;107:e1-e10

28. Bhonsle RB, Murthi PR, Gupta PC, Mehta FS. Reverse dhumti smoking in Goa-an epidemiological study of 5449 villages for oral precancerous lesions. Indian J Cancer 1976; 13, 301-5.

29. S.C.Gupta,Mangal Singh, Sanjay Khanna, Sachin Jain: Oral Submucous Fibrosis withits possible effect on Eustachian tube functions: A tympanometric study,Indian Journal of Otolarygology and Head and Neck Surgery, vol 56,No. 3, July/Sept 2004.

30. Paymaster JC. Cancer of the buccal mucosa; a clinical study of 650 cases in Indian patient. Cancer 1956;9:731-5

31. Pindborg JJ, Zachariah J. Frequency of oral submucous fibrosis among 100 south Indians with oral cancer. Bull WHO 1965;30:750-3.

32. Pindborg JJ, Murti PR, Bhonsle RB, Gupta PC, Daftary DK, Mehta FS. Oral submucous fibrosis as a precancerous condition. Scand J Dent Res 1984;92(3):224-229.)

33. Pindborg JJ, Sirsat SM. Oral submucous fibrosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1966;22(6):764-779.

34. Pindborg JJ, Mehra FS, Daftary DK. Incidence of oral cancer among 30,000 villages in India in a 7 year follow up study of oral precancerous lesions: Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1975;3:86-8.

35. Khanna JN, Andrade NN. Oral submucous fibrosis-a new concept in surgical management. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1995;24:433-9.

36. S. M. Haider, A. T. Merchant,F. F. Fikree,M. H. Rahbar: Clinical and functional staging of oral submucous fibrosis, British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery;2000 38, 12-15

37. Ajit Auluck, Miriam P. Rosin, Lewei Zhang, Sumanth KN, Oral Submucous Fibrosis, a Clinically Benign but Potentially Malignant Disease: Report of 3 Cases and Review of the Literature, JCDA, October 2008, Vol. 74, No. 8,735-740

38. Lai DR, Chen HR, Lin LM, Huang YL, Tsai CC. Clinical evaluation of different treatment methods for oral submucous fibrosis. A 10 year experience with 150 cases. J Oral Pathol Med 1995;24:402-6.

39. SHARMA J K , GUPTA AK, MUKHIJA RD, NiGAM P. Clinical experience with the use of peripheral vasodilator in oral disorders. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1987; 16; 695 9.

40. Ward A, Clissold SP: Pentoxifylline: a review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and its therapeutic efficacy, Drug Eval 34: 50-97, 1987

41. Edwards MJ, Abney DL, Miller FN: Pentoxifylline inhibits interleukin-2 induced leukocyte-endothelial adherence and reduces systemic toxicity, Surg 110: 199-204,1991.

42. R Rajendran, Vidya Rani, Saleem Shaikh: Pentoxifylline therapy : A new adjunct in the treatment of oral submucous fibrosis, 2006,Vol: 17 ,4, 190-198.

43. Singh M, Krishanappa R, Bagewadi A, Keluskar V. Efficacy of oral lycopene in the treatment of oral leukoplakia. Oral Oncol 2004;40:591-6.

44. Kitade Y, Watanabe S, Masaki T, Nishioka M, Nishino H. Inhibition of liver fibrosis in LEC rats by a carotenoid, lycopene or a herbal medicine, Sho-saiko-to. Hepatology Research 2002; 22:196-205.

45. Kumar A, Bagewadi A, Keluskar V, Singh M. Efficacy of lycopene in the management of oral submucous fibrosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. Feb 2007;103(2):207-13

46. Borle RM, Borle SR. Management of oral submous fibrosis; A conservative approach. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1991; 49; 788-91.

47. Gupta D, Sharma SC. Oral submucous fibrosis - a new treatment regimen. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1988; 46; 830-3.

48. Sur TK, Biswas TK, Ali L, Mukherjee B. Anti-inflammatory and anti-platelet aggregation activity of human placental extract. Acta Pharmacol Sin. Feb 2003;24(2):187-92

49. Kakar PK. Puri RK. Venkatachalam VP. Oral submucous fibrosis-treatment with hyalase. J Laryngol Otol 1985; 99; 57-9

50. Haque MF, Meghji S, Nazir R, Harris M. Interferon gamma (IFN-gamma) may reverse oral submucous fibrosis. J Oral Pathol Med. Jan 2001;30(1):12-21

51. N.Samman The buccal fat pad in oral reconstruction. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1993:22:2-6

52. M.A.Amin Use of buccal fat pad in the reconstruction and prosthetic rehabilitation of oncological maxillary defects Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 43:148-154, 2005

53. Yeh CJ. Application of the buccal fat pad to the surgical treatment of oral submucous fibrosis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1996;25:130-3.

54. Zhang HM Anatomical structure of the buccal fat pad and its clinical adaptations. Plast Reconstr Surg 2002 Jun: 109(7):2509-2518

55. Shobha Nataraj 1, Yadavalli Guruprasad 2, Jayaprasad .N.Shetty: A Comparative Clinical Evaluation of Buccal Fat Pad and Collagen in Surgical Management of Oral Sub mucous Fibrosis. Archives of Dental Sciences,2011, Vol.2, Issue 2; 15-22

56. Gupta RL .Fate of collagen sheet cover for artificially created raw areas (exptal study) Int J of Surg, vol 40;1978 (a) 641-645

57. R .Mitchell A New Biological Dressing for areas Denuded of Mucous membrane. Br Dent J 1983; 155: 346-348

58. Dino BR, Eufemio G G , Devilla MS. Human amnion; the establishment of an amnion bank and its practical applications in surgery. J Phil Med A.K.WC 1965; 41; 890-8.

59. Colocho G, Graham WP, Greene A E , Matheson DW, Lynch D. Human amniotic membrane as a physiologic wound dressing. Arch Surg 1974; 109; 370-3.

60. Alexander D.Rapidis. The use of the Buccal fat pad for Reconstruction of oral defects: review of literature and report of 15 cases.J Oral Maxillofac; 58:158-163, 2000.

61. Mokal NJ, Raje RS, Ranade SV, Prasad JS, Thatte RL. Release of oral submucous fibrosis and reconstruction using superficial temporal fascia flap and split skin graft- a new technique. Br J Plast Surg 2005;58:1055-60.

62. Kavarana HM, Bhatena HM. Surgery for severe trismus in submucous fibrosis. Br J Plast Surg 1987;40:407-9.

63. Borle RM, Nimonkar PV, Rajan R: Extended nasolabial flaps in the management of oral submucous fibrosis. The British journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery, 2009; 47(5) :382-385

64. Anisha Maria, Yogesh Sharma, Preeti Kaur: Use of Nasolabial Flap in the Management of Oral Submucous Fibrosis - A Clinical Study People's Journal of Scientific Research Vol. 4(1), Jan. 2011, 28-30

65. R. Martin Granizo Use of buccal fat pad to repair Intraoral defects: review of 30 cases. Br J Maxillofac Surg; 35: 81-84, 1997

66. Wei FC, Chang YM, Kildal M, et al. Bilateral small radial forearm flaps for the reconstruction of buccal mucosa after surgical release of submucosa fibrosis: a new, reliable approach. Plast Reconstr Surg 2001;107:1679.

67. Lee JT, Cheng LF, Chen PR, et al. Bipaddled radial forearm flap for the reconstruction of bilateral buccal defects in oral submucous fibrosis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2007;36:615.

68. Jung-Ju Huang, Chris Wallace, Jeng-Yee Lin, Chung-Kan Tsao, Huang-Kai Kao, Wei-Chao Huang, MingeHuei Cheng, Fu-Chan Wei: Two small flaps from one anterolateral thigh donor site for bilateral buccal mucosa reconstruction after release of submucous fibrosis and/or contracture; Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery (2010) 63, 440-445

69. Omura S, Mizoki. A newly developed collagen/silicon bilayer membrane as a mucosal substitute-a preliminary report. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1997;35:85-91.

70. Nayak DR, Mahesh SG, Aggarwal D, Pavithran P, Pujary K, Pillai S Role of KTP-532 laser in management of oral submucous fibrosis J Laryngol Otol. 2009 Apr;123(4):418-21. Epub 2008 71.FRAME JW. Carbon dioxide laser surgery for benign oral lesions. Br Dent J 1985; 158; 125-8. |