Introduction:

The term “oral cancer” includes all malignancies occurring in the tongue, lips, buccal mucosa, floor of mouth, palate, pharynx and other ill-defined sites within the lip, oral cavity, and pharynx[1]. Globally oral cancer represents an incidence of 3 percent in males and 2 percent in female of all malignant neoplasms, Oral cancer has one of the lowest survival rates - 50 percent, within a five-year period[2]. Cancer is amongst the ten most commonest cause of mortality in developing countries including India. Oral cancer is major problem in India and accounts for 50-70% of all cancer cases diagnosed compared to 2-3 % in UK and USA. [3]

The World Health Organization reported oral cancer as having one of the highest mortality ratios amongst all malignancies. Unfortunately, most oral cancers lack early signs, and despite improvements in diagnostic and treatment options, the prognosis of patients with oral malignancies has remained poor.[3] In essence, this poor outcome is related to the majority of patients presenting at an already advanced stage of disease at the time of diagnosis with over 60% presenting in stage III and IV.[3] This may be due to an incomplete understanding or awareness that even small asymptomatic lesions can have significant malignant potential one approach to solve this problem is to improve the ability of the dentist to detect potentially malignant lesions or cancerous lesions at it early stage.[4] This can be achieved by increasing the public awareness about regular oral screening and also by development and use of diagnostic aids that would help the dentist in identifying the malignant potential lesions more readily.[5] The UK Working Group on screening for oral cancer and precancer concluded that the most suitable screening for oral cancer and precancer is a thorough and methodical examination in good lighting of the mucosal surfaces of the oral cavity.[6] Since 1960, many studies have focused on the important role of toluidine blue dye as an adjunct to the detection of oral cancer.[7],[8] Two emerging advanced technology methods for use in oral cancer screening programs are fluorescent imaging and brush biopsy.[9],[10] Despite development of different methods for screening of oral cancer, limitations of all these diagnostic aids still persist. This paper will review the different diagnostic aids available for oral cancer screening and their pitfalls or limitations in diagnosis.

Screening:

Screening has been defined as ‘the application of a test or tests to people who are apparently free from the disease in question in order to sort out those who probably have the disease from those who probably do not. Screening involves checking for the presence of disease in symptom free individuals.[11]

Criteria for implanting screening:In UK The National Screening Committee lists 22 criteria that should be met before a screening programme is introduced.[12] These criteria were taken from work of Wilson and Jungner.[11] The criteria are summarized in Table 1. If a lesion meets any 3 criteria, then screening programme should be implemented.[13]

| Table 1: Summarized Criteria For The Implementation Of A Screening Programme

|

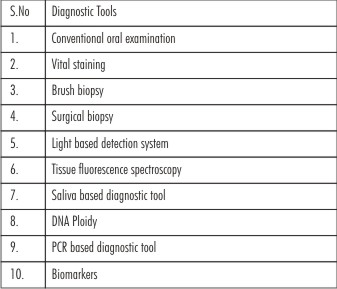

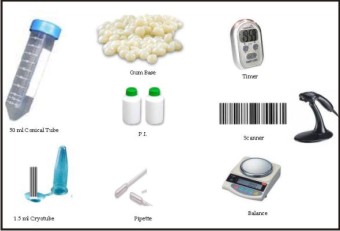

Current diagnostic aids for oral cancer screening:(Table 2)

| Table 2: Diagnostic Tools

|

1. Conventional Oral Examination:it require only mouth mirror and normal light source. Oral precancer and cancer demonstrate a wide range of clinically detectable alterations that may range from an early subtle change in surface texture, color or elasticity to more obvious lesions.[16] Surface changes may include red or white lesions with some associated symptoms. Mucosal texture may show firmness or indurations upon palpation.[17] (Figure 1)

| Figure 1: Visual Examination

|

Pitfalls:

i. Successful only in certain anatomic locations, for example tongue, lip and buccal mucosa. Cancers of posterior part of tongue or soft palate are difficult to examine.

ii. Cannot identify all potentially premalignant lesions.

iii. Not accurate in detecting small proportion of biologically relevant lesions taht are likely to be premalignant.

iv. Depend on individual prediction

2. Vital staining: Toluidine blue also called as Tolonium Chloride is a vital dye that stains Nucleic Acid and abnormal tissue. It is one of the oldest techniques for detecting abnormalities of cervix and oral cavity.[18] It is useful in demarcating the extend of the lesion thus helping in determining the extent of surgery.[18],[19] (Figure 2)

| Figure 2: Vital Staining

|

Pitfall:

i. Most of the dye positive carcinoma are clinically visible

ii. Histological diagnosis is rarely used as gold standard

iii. Method vary from single rinse to double rinse and painting

iv. Confusion persists over inclusion of pale stained lesion as positive or negative.[19]

3. Brush biopsy: The brush biopsy (oral CDX) was first introduced in 1999 as potential oral cancer case finding device. It is useful when the practitioner is uncertain whether the lesion requires a scalpel or punch biopsy. A transepithelial sample of cells from mucosal lesions representing superficial, intermediate and parabasal layers of epithelium is collected with the help of Oral CDX brush in this method.[20],[21] (Figure 3)

| Figure 3: Brush Biopsy

|

Pitfalls:

i. Intermediate diagnostic step as scalpel biopsy must follow when results are positive

ii. More incidence of false positive results

iii. Technique is less accurate.[22]

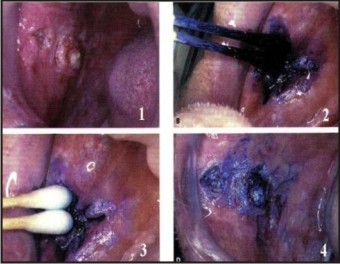

4. Surgical Biopsy: It includes scalpel biopsy or punch biopsy. The specific indication for surgical biopsy rather than brush biopsy would include a highly suspicious lesion, an obvious cancer or a lesion in a person at high risk for whom a definitive diagnosis would be necessary as soon as possible.[23] (Figure 4)

| Figure 4: Surgical Biopsy

|

Pitfalls:

i. Cannot be done in patient allergic to local anaesthetics

ii. Result in disfigurement of the organ

iii. Take time in healing of the wound

iv. Possible false positive result

v. Psychological implication to the patients[24]

vi. Dissemination of cancer cell[25]

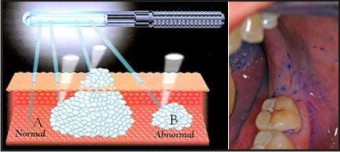

5. Light Based Detection System : tissue reflectance has been used for many years as an adjunct in the examination of the cervical mucosa for “Aceto white” premalignant and malignant lesions. But recently this technique has been adopted for use in oral cavity and is marketed as Vizilite Plus and MicroLux DL. The MicroLux unit offers a reusable, battery-powered light source whereas ViziLite Plus uses a disposable light packet.[26],[27] The 1% acetic acid wash is used to help remove surface debris which results in mild cellular dehydration and increases the visibility of epithelial cell nuclei. Normal epithelium appears lightly bluish under blue - white illumination whereas abnormal epithelium appears distinctly white (Acetowhite).[28] (Figure 5)

| Figure 5: Light Based Detection System

|

Pitfalls:

i. Lack of diagnostic correlation with biopsy finding

ii. Can not differentiate between malignant and benign lesions

iii. Chemiluminescent light produce reflection that make visualization more difficult[28],[29]

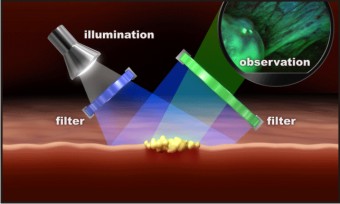

6. Tissue Fluorescence Spectroscopy : Potential use of autofluorescence as cancer diagnostic aid was observed approximately 30 years ago. There has been considerable interest in the technologies of both fluorescence imaging and spectroscopy in cancer screening for a number of anatomic sites including the oral cavity.[30] Fluorescence spectroscopy involves the exposure of tissues to various excitation wavelengths so that subtle differences between normal and abnormal tissues can be identified. The concentration of fluorophores changes due to presence of cellular alterations, which affects the absorption and scattering of light in the tissue, thus results in change in color that can be observed visually. The VELscope which is marketed for use in oral cancer screening is a portable device that allows for direct visualization of the oral cavity.[31] (Figure 6)

| Figure 6: Tissue Fluorescence Spectroscopy

|

Pitfalls:

i. Not feasible to scan the entire oral cavity using the small optical fibers required for spectroscopy.

ii. More variables like combinations of wavelength, methodology of fluorescence analysis have to be tested and considered which lead to controversial and unclear result.[30]

iii. Not suitable to detect new lesions or to demarcate large lesion.

7. Saliva Based Oral Cancer Diagnostic Aids:Saliva from patients has been used in a novel way to provide molecular biomarkers for detection of oral cancer. Saliva acts as a mirror of the body which reflects virtually the entire spectrum of normal and disease states and its use as a diagnostic fluid meets the demands for non-invasive, an inexpensive, and accessible diagnostic tool.[32] The utility of salivary transcriptome diagnostics are helpful in the detection of oral cancer. Promoter hypermethylation pattern of TSG p16, O6 methyl guanine DNA methyltransferase and health associated protein kinase are identified in saliva of patients with cancer of head and neck.[33] (Figure 7)

| Figure 7: Saliva Based Oral Cancer Diagnostic Tools

|

Pitfalls:

i. Presence of low concentration of tumor markers makes the diagnosis difficult.

ii. Difficulty in isolation of minor components of saliva.[33],[34]

8. DNA based diagnostic tools:DNA changes are observed in cancerous lesions which occur due to mutation. DNA analysis can be done by DNA ploidy or by Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR).[35] In DNA ploidy measurement of nuclear DNA content is done which provide measurement of gross genetic damage. The nuclear DNA distribution patterns can be analyzed by flow cytometry showing different rates of dysplasia.[36] PCR can be used to detect mutation in cancer associated oncogens, tumor suppressor genes and aids as an important detection tool. [35] (Figure 8)

| Figure 8: Dna Ploidy

|

Pitfalls:

i. Quantity of specimen should be more for examination.

ii. Contamination and amplification artifacts may give rise to difficulties in interpretation.[35],[37]

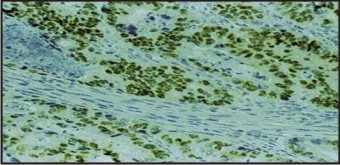

9. Biomarkers: Tumor markers such as p53, ki67, bcl2 or EGF are present in blood circulation, body fluids, cell membrane and cell cytoplasm and are released by cancer cells or produced by the host in response to cancerous substances. These biomarkers can be used for diagnosis of cancer.[38] (Figure 9)

| Figure 9: Biomarkers

|

Pitfalls:

i. Different types of cancerous lesions give positive result with same biomarkers.

ii. Tests are very expensive and complex.[28]

Conclusion:

Diagnosis of oral cancer and precancerous lesions remain a challenge for dental profession especially in diagnosis, evaluation and treatment of early phase alteration or frank disease. Screening and early detection in populations at risk have been proposed to decrease both the morbidity and mortality associated with oral cancer. There is a growing realization that some premalignant and early cancerous lesions are not readily detectable to the naked eye, so additional screening aids for oral cancer are desperately needed. In the last decade, there has been a dramatic increase in the development of potential oral cancer screening or case finding tools. Each of them may hold promise in selected clinical settings but unfortunately no technique or technology available till date has provided definitive evidence to suggest that it improves the sensitivity or specificity of oral cancer screening. Hence more research and studies are required to improve the efficacy of all the available diagnostic aids.

References:

1. Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Estimating the world cancer burden: Globocan 2000. Int J Cancer 2001;94(2):153–6.

2. American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures; 2005. <http://www.cancer.org/docroot/STT/stt_0.asp>.

3. Greenlee RT, Hill-Harmon MB, Murray T, Thun M. Cancer statistics 2001. CA Cancer J Clin 2001;51:15-36.

4. Day GL, Blot WJ. Second primary tumors in patients with oral cancer. Cancer 1992;70(1):14–9.

5. Ferlay J, Bray F, Pisani P, Parkin DM. GLOBOCAN 2000, cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide, Version 1.0. Lyon: IARC Press, 2001.

6. Zakzerwska JM, Hindle I, Speight PM. Practical considerations for the establishment of an oral cancer screening programme. Community Dent Health 1993;10(Suppl1):79-85.

7. Eliezri YD. The toluidine blue test: an aid in the diagnosis and treatment of early squamous cell carcinomas of mucous membranes. J Am Acad Dermatol 1988; 18:1339-49.

8. Moyer GN, Taybos GM, Pelleu GB. Toluidine blue rinse: potential for benign lesions in early detection of oral neoplasms. J Oral Med 1986;41:111-3.

9. Christian DC. Computer-assisted analysis of oral brush biopsies at an oral cancer screening program. J Am Dent Assoc 2002;133:357-62.

10. Onizawa K, Saginoya H, Furuya Y, Yoshida H. Fluorescence photography as a diagnostic method for oral cancer. Cancer Lett 1996;108:61-6.

11. Wilson JMG JY. Principles and practice of mass screening for disease. Public Health Pap, No. 34; 1968.

12. UK National Screening Committee, Criteria for appraising the viability, effectiveness and appropriateness of a Screening programme. <http://www.nsc.nhs.uk/uk_nsc/uk_ nsc_ind. htm>.

13. Jaeschke R, Guyatt G, Sackett DL. Users’ guides to the medical literature. III. How to use an article about a diagnostic test. A. Are the results of the study valid? Evidence-based medicine working group. JAMA 1994;271(5):389–91.

14. Woolgar J. A pathologist's view of oral cancer in the North West.Br Dent J1995;54:14-16.30.

15. Sciubba JJ. Oral cancer. The importance of early diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol 2001;2:239-251.

16. Whited JD, Grichnik JM. The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have a mole or a melanoma? JAMA 1998;279(9):696–701.

17. Rampen FH, Casparie-van Velsen JI, van Huystee BE, KiemeneycLJ, Schouten LJ. False-negative findings in skin cancer and melanoma screening. J Am Acad Dermatol 1995;33(1):59–63.

18. Mashberg A: Final evaluation of tolonium chloride rinse for screening of high-risk patients with asymptomatic squamous carcinoma. J Am Dent Assoc 1983, 106:319-323.

19. Epstein JB, Feldman R, Dolor RJ, Porter SR: The utility of tolonium chloride rinse in the diagnosis of recurrent or second primary cancers in patients with prior upper aerodigestive tract cancer. Head Neck 2003, 25:911-921.

20. Frist S: The oral brush biopsy: separating fact from fiction. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2003, 96:654-5.

21. Eisen D, Frist S: The relevance of the high positive predictive value of the oral brush biopsy. Oral Oncol 2005, 41:753-755.

22. Sciubba JJ: Improving detection of precancerous and cancerous oral lesions. Computer-assisted analysis of the oral brush biopsy. U.S. Collaborative OralCDx Study Group. J Am Dent Assoc 1999, 130:1445-1457.

23. Mehrotra R, Gupta D. Exciting new advances in oral cancer diagnosis: avenues to early detection. Head and Oncology.2011;3(31)

24. Holmstrup P, Vedtofte P, Reibel J, Stoltze K: Oral premalignant lesions: is biopsy reliable? J Oral Path Med 2007, 36:262-6.

25. Kusukawa J, Suefuji Y, Ryu F, Noguchi R, Iwamoto O, Kameyama T: Dissemination of cancer cells into circulation occurs by incisional biopsy of oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med 2000, 29:303-7.

26. Ram S, Siar CH: Chemiluminescence as a diagnostic aid in the detection of oral cancer and potentially malignant epithelial lesions. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2005, 34:521-527.

27. Farah CS, McCullough MJ: A pilot case control study on the efficacy of acetic acid wash and chemiluminescent illumination (ViziLite trade mark) in the visualisation of oral mucosal white lesions. Oral Oncol 2007, 43:820-824.

28. Satoskar S, Dinkar A. Diagnostic aids in early cancer detection: a review. J Indian Academy of Oral Med & Radiol. 2006;18:82-9

29. Poh CF, Zhang L, Anderson DW, et al. Fluorescence visualization detection of field alterations in tumor margins of oral cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res 2006;12(22):6716-6722.

30. De Veld DC, Witjes MJ, Sterenborg HJ, Roodenburg JL: The status of in vivo autofluorescence spectroscopy and imaging for oral oncology. Oral Oncol 2005, 41:117-131.

31. Lingen MW, Kalmar JR, Karrison T, Speight PM: Critical evaluation of diagnostic aids for the detection of oral cancer. Oral Oncol 2008, 44:10-22.

32. Li Y, Zhou X. Salivary transcriptome diagnostic for oral cancer detection. Clin cancer Res. 2004;10:8442-50

33. S Crispian, Jose V. Oral cancer: Current and future diagnostic techniques. Am J Dentistry.2008;21: 199-209.

34. Osuna T, Hopkins S. Diagnostic aids in early oral cancer detection- a review. J Indian Academy of Oral Med & Radio.2006l;18: 82-9.

35. Bradley G, Odell EW, Raphael S, Ho J, Le LW, Benchimol S, Kamel-Reid S: Abnormal DNA content in oral epithelial dysplasia is associated with increased risk of progression to carcinoma. Br J Cancer 2010, 103(9):1432-42.

36. Maraki D, Becker J, Boecking A: Cytologic and DNA cytometric very early diagnosis of oral cancer. J Oral Pathol Med 2004, 33:398-404.

37. Handschel J, Oz D, Pomjanski N, Depprich R, Ommerborn MA, Braunstein S, Kübler NR, Meyer U, Böcking A: Additional use of DNA-image cytometry improves the assessment of resection margins. J Oral Pathol Med 2007, 36(8):472-5.

38. Mehrotra R, Vasstrand EN, Ibrahim SO: Recent advances in understanding carcinogenicity of oral squamous cell carcinoma: from basic molecular biology to latest genomic and proteomic findings. Cancer Genomics Proteomics 2004, 1:283-94.

39. Dolan RW, Vaughan CW, Fuleihan N. Symptoms in early head and neck cancer: an inadequate indicator. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1998;118:463.

40. Ellison MD, Campbell BH. Screening for cancer of the head and neck: addressing the problem. Surg Oncol Clin N Am 1999;8:725-34.

41. Lippman SM, Hong WK. Second malignant tumors in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: the overshadowing threat for patients with early-stage disease. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1989;17(3):691–4.

|