Introduction

The oral cavity is considered the sentinel or an early warning systemfor health and diseases. Presence of lesions may cause discomfort or pain, interfering in normal functions of mastication, swallowing and speech or may produce symptoms of halitosis, xerostomia, or oral dysesthesia. This may further affect the quality of life in terms of social well-being[2]. Incidentally, most lesionsencountered in routine clinical examinations are asymptomatic, emphasizing the need of a thorough clinical examination as an opportunity for early diagnosis of a disease.

Adolescents are at crossroads between childhood and adulthood and it is unclear whether the pattern of oral diseases in this group resembles that of children or that of adults.[4] Despite World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations, the epidemiologic literature about children and adolescents in this field is quite limited.[5] Studies have been conducted mainly in adults or in populations at high risk for specific lesions. A few studies reported are of selected mucosal alterations confined to specific anatomic regions or lesion.Also, lack of epidemiologic data may often lead to many soft tissue diseases of oral cavity being overlooked. Furthermore, epidemiology of oral mucosal lesions in adolescent has received limited attention as compared to epidemiological data for prevalence of caries in children or periodontal diseases in adults.[7]

In recent years however, health professionals and the general public at large have been made more aware of importance of oral mucosal pathologies.[1] Understanding the distribution, etiology, natural history and epidemiology of oral mucosal pathologies is essential to promotionof primary prevention, early diagnosis, prompt treatment and the provision of appropriate health services.[9]

The present study is aimed at estimating the prevalence of oral mucosal lesions in children and adolescents visiting hospitals of Western Uttar Pradesh. It can also be used to estimate the prevalence rate among different groups based on age, gender, geographic location, socioeconomic status, educational level and nutritional status.

Materials And Method

The present study was a descriptive epidemiological period-prevalence study on 2000 subjects (up to 18 years of age) visiting the department of Pediatric Dentistry of I.T.S Dental College, Muradnagar and Dental and Dermatology Department of SVBP Hospital, LLRM Medical College, Meerut examinedover a period of two consecutive years between December ’09 to March’11.

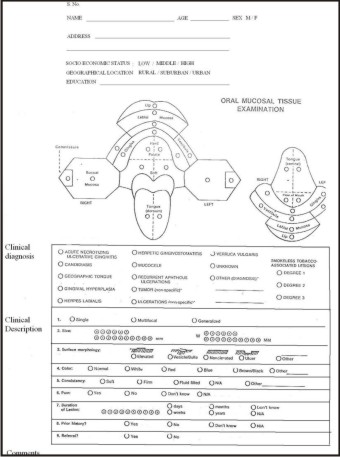

All the subjects were interviewed and examined clinically on a dental chair, in a controlled environment after obtaining the necessary consent and approval from hospital ethical committee. A customized proforma for recording of examination findings was used along with an assessment form developed by Roed-Petersen and Renstrup and later on modified by Kleinman DV et al in 1994. Clinical diagnostic criteria for lesions based on the World Health Organization’s Manual of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Injuries and causes of Deathwere followed in accordance with Kleinman DV et al1 study (Figure 1).Concomitant occurrence lesions with mucocutaneous involvement were assessed by an experienced dermatologist of L.L.R.M Medical College and after due consultation diagnoses were formulated.

The data obtained was tabulated and subjected to statistical analysis utilizing the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 10.0. The tests of significance applied were Univariate Logistic Regression analysis and Pearson chi-square test. The odds ratio was calculated to determine the relative significance for the occurrence of lesions among different variables. p-value (<0.05) was considered significant with a 95% confidence interval for estimating the risk of individual lesions in the population.

Results

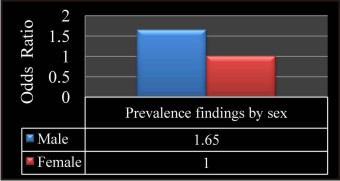

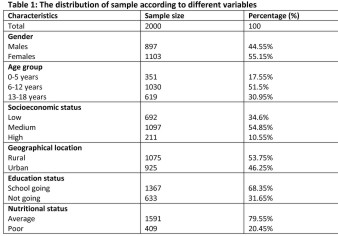

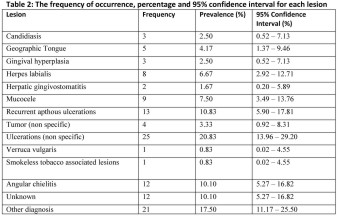

Sample population comprised of 2000 children and adolescents out of which 897 (45.55%) were males and 1103 (55.15%) were females. Mean age of overall population was 9.25 years and 120 subjects had oral lesions with an overall prevalence rate of 6%.Twelve cases out of the total patients with lesions (10%) had associated skin disorders. Table 1 depicts frequency distribution of sample in various age group, geographic location socioeconomic status, education level and subjective nutritional status evaluated by the investigator. Maximum numbers of subjects were in age group of 6-12years and were school going coming from rural area belonging to mid-socioeconomic status. Further analysis showed males having significantly greater number of lesions as compared to females (OR=1.658). Table 2 shows frequency distribution for the occurrence of individual lesions observed in sample population with a confidence interval of 95%.

| Figure 1

|

| Figure 2

|

| Figure 3

|

|

|

|

|

Discussion

The epidemiologic literature on oral mucosal lesions in children is limited when compared to that of dental caries and periodontal diseases. Most of the studies conducted in past have been in adults or in populations at high risk for specific lesions of interest.

In the present study, 2000 subjects (age < 18years) were examined for the presence of oral mucosal lesions in an appropriate dental set up giving a little chance of missing out the lesion if present. A6% prevalence rate of oral mucosal lesions in children and adolescents was reported. However, literature lists a wide range of prevalence findings varying from 2.3% to 38.9%. Shulman JD[22] described the results of the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994 in U.S after screening 10,030 individuals with ages ranging from 2 to 17 years and reported a prevalence of 10.26%. Mathew et al[3] reported a much higher rate of prevalence after examining 1190 patients of different age groups in a dental hospital setting in Manipal, India. They found a prevalence of 16.88% (n=243) in the age group of 2-20 years and an overall prevalence of 41.2 % in the entire population. On the other hand Sudhakar S, B Praveen Kumar, Prabhat MPV[26] evaluated the prevalence of oral mucosal lesions in Eluru, Andhra Pradesh and found a prevalence rate of 1.2% in the age group of 1-15 years and 49.06% in overall population. This variation could be attributed to diverse clinical settings with regards to subject selection and diagnostic criteria opted by different researchers.

Gender disparity in presence of oral mucosal lesions in children was observed by Kleinman DV et al[1] where males showed a significantly higher prevalence of oral lesions in comparison to females. The present study also reported 1.65 times more likelihood for males than females in presentation of an oral lesion.

Prevalence of oral mucosal lesions seems to increase with age.[3],[20], [22], [26] Bessa CFN et al[20] found a higher lesion prevalence rate in a group of older children. Kleinman DV et al and Shulman JD[22] observed lesion prevalence to be almost double in 17 year olds. The present study also showed increase of lesion occurrence with advancing age but results were statistically insignificant. Factors contributing to this effect might include prolonged or increased exposure with age to a wider range of risk factors such as stress, tobacco, medications and prosthetic devices.

Maximum number of subjects in the present study were in the age range of 6-12 years (n=1030) in which 5.72% prevalence rate was reported. While the prevalence rate of 5.12% and 6.94%.was found in children up to the age of 5 years and adolescents (13-18years) respectively. Prevalence rate in the present study was found to be greater than the prevalence rate found by Bezerra S and Izabel C[16] (2.3%) among children up to 5 years of age in Brazil and much lesser in contrast with study done by Arendorf TM and Van der Ross R[15] (32.9%) in South Africa and Bessa CFN et al[20] (24.9%) in Brazil. Garcia Pola MJ[6] investigated the prevalence of oral lesions in 6-year olds in Oviedo, Spain and found 38.9% prevalence which was much higher than the prevalence rate observed in the corresponding age group in the present study. On the other hand Bessa CFN et al[20] also found a higher prevalence of 30.3% for similar age group in Brazil. Prevalence findings of the present study were much less as compared to a study done by Parlak AH[5] that reported a prevalence of 26.3% in Turkish adolescents as compared to 6.94% in the present study.

The socioeconomic status was recorded for evaluation of any difference in the occurrence of oral mucosal lesions among the low, medium and high socioeconomic strata. An increasing trend was observed for the presence of oral mucosal lesions from high to low socioeconomic status, but the difference was not significant. These findings were in agreement with the study done by Crivelli et al[7] that compared school children from two different socioeconomic strata for difference in prevalence of oral lesions and found inconclusive results. Similarly no statistical difference existed in the present study with regards to geographic location (rural vs urban) and occurrence of oral mucosal lesions. This quashedthe assumption that lack of awareness, compromised oral hygiene status and nutritional deficiencies prevails among children belonging to rural area can have an effect on oral pathology.

Nutritional deficiencies have been related to many lesions like angular cheilitis, recurrent aphthous ulcerations and candidiasis. To determine the nutritional status of the individual,a verbal interview of the parent or the child himselfregarding the quality and quantity of diet intake was done. Resultsshowed no difference in general prevalence between children with an average or poor nutritional status. Similarly insignificant results were observed with regards to educational status of child in the present study.

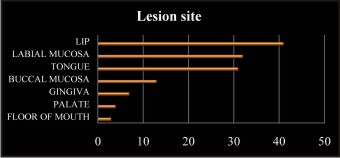

Lip (34.17%) was the most commonly affected site followed by labial mucosa (26.67%), tongue (25.83%), buccal mucosa (10.83%), gingival (5.83%), palate (3.3%) and floor of mouth (2.5%) in decreasing order. Reason of a higher occurrence in lip lesions could be related to higher episodes of traumatic ulcer in this location and/or because of inclusion of angular cheilitis lesions under the category of lip. Similar findings were observed by Shulman JD[22] who also found lip (30.7%) to be the most common affected site. In contrast, Klienman DV et al[1] reported maximum number of lesions on buccal and labial mucosa (58.5%). Moreover, most lesions (84.16%) were confined to only one distinct anatomic location of the oral cavity, an observation also noted by Kleinman DV et al[1] where a similar trend was seen in 78.4% of their population.

Individual lesion prevalence was not considered in the present study due to sample size constraints (small sample) though risk estimates were calculated for their occurrence with 95% confidence interval.

Ulcerations (non specific)

The most common lesion reported was non specific ulcerations which formed 20.83% of total lesions. It included traumatic ulcers or any ulcer that could not be attributed to one of the other ulcerative conditions. The prevalence of non specific ulcerations or traumatic lesions has been reported by Crivelli et al (1.41%) in Argentina, Kleinman DV, Swango PA, Pindborg JJ (0.09%) in United States, Arendroff TM (2.5%) in South Africa, Garcia-Pola et al (12.17%) in Spain and Bessa et al (2.23%) in Brazil.[21]

Majority of the traumatic lesions or ulcers (62.9%) were seen in children who had history of LA administration during a dental procedure. These types of lesions were observed mostly in childrenaged 6-12 years and decreased with increasing age. The younger children are more prone to lip biting under anesthesia because of limited comprehension of instructions and anxiousness about the numbness caused by local anesthesia. College C, Feigal R, Wandera A and Strange M[17] reported that 13% of children patients experienced post operative soft tissue trauma and it was maximum for the younger age group.

Remaining lesions under this category were non-specific ulcerations and traumatic lesions due to a fall, cheek biting, or due to toothbrush abrasion or by local injuries.

Recurrent aphthous ulcerations

The second most common lesion reported was recurrent aphthous ulcerations comprising of 10.83% of total lesions. It is an oral ulcerative condition characterized by recurring, painful, solitary or multiple ulcers, typically covered by a white to yellow pseudomembrane and surrounded by an erythematous halo. Prevalence of recurrent aphthous ulcerations reported in previous studies was 1.23% by Kleinman DV,Swango PA, Pindborg JJ in United States, 10.87% by Crivelli et al in Argentina, 4.08% by Garcia-Pola et al in Spain and 1.57% by Bessa et al in Brazil.[21]

The aphthous ulcers were mostly observed in adolescents (10 out of 13) from urban areas and attending schools. Kleinman DV et al[1] and Shulman JD[22] observed recurrent aphthous ulcerations in similar age group. It was observed that recurrent aphthous ulcerations were reported mostly among children belonging to high and medium socioeconomic strata. A similar trend was observed in a study done by Crivell et al in which prevalence of RAU was significantly higher in school children on high socioeconomic status as compared to schoolchildren of low socioeconomic status. He ascribed this prevalence difference to stress arising from greater expectations and more demanding responsibilities on students belonging to high socioeconomic status.

All the lesions under this category were unilateral, at a single site and painful (symptomatic). There was no difference between genders as both males and females were equally affected. All the children affected had an average nutritional status and were not suffering from nutritional deficiencies.

Angular cheilitis

Angular cheilitis comprised 10.10% of the total lesions found in the present study. This prevalence varies from the findings of Bessa CFN (0.08%) in Brazil, A Parlak et al (9%) in Turkey, Garcia Pola (2.08%) in Spain, Crivelli Mr (3.54%) in Argentina to Arendrof Tm (15.1%) in South Africa in previous studies. [5], [21]

Angular cheilitis was more commonly observed in people of low socioeconomic status (Crivelli et al, 1988). This observation was true for present study as 10 out of 13 patients diagnosed with angular cheilitis belonged to lower socioeconomic group and had a poor nutritional status.

Mucocele

A mucocele is an area of mucin spillage in soft tissue resulting from rupture of a salivary gland duct. The typical clinical presentation is a bluish, dome-shaped, fluctuant mucosal swelling. The incidence of mucoceles is generally high, 2.5 lesions per 1000 patients[27]. In the present study 9 patients had mucocele. 8 out of 9 patients of mucocele belonged to age 6-12 years group and 7 out 9 were males (77.7%).

Recurrent herpes labialis

Recurrent herpes labialis was reported in 8 patients comprising 6.67% of total lesions. Primary infection with herpes simplex is asymptomatic in the majority of children but when symptomatic it presents as acute gingivostomatitis. 2 cases (1.67%) of primary herpetic gingivostomatitis were also seen in the present study.Herpes labialis is the reactivation of the primary infection, often following a prodromal period, and lesions present early as clusters of vesicles on the lip which soon burst and scab over.

Crivelli et al[7] observed herpes labialis prevalence could be correlated to socioeconomic status as he found significantly higher prevalence of the condition in school children belonging to lower socioeconomic status. 5 out of 8 children belonged to low socioeconomic status (62.5%) groupin the present study and 6 out of 8 were males (75%).

Geographic tongue

Geographic tongue comprised of 4.17% of total lesions in the present study. It appears to occur more commonly in children and frequency decreases with age.3 out of 5 children (60%) belonged to age groupof 0-5 yearsin the present study. Crivelli et al[7] observed higher prevalence in children belonging to high socioeconomic status which was not true for the present study as 4 out 5 belonged to medium socioeconomic (80%) status while 1 belonged to low socioeconomic status.

Tumors (non specific)

Non specific tumors comprised 3.33% of total lesions. Two cases of hemangioma, one lymphangioma and one papilloma were reported in the present study. Cases of lymphangioma and papilloma were present on tongue where as one case of hemangioma affected lips and other affected buccal mucosa

Candidiasis

Candidiasis was present in 3 cases making 2.5% of total lesions. Oral candidiasis is an opportunistic infection of oral cavity and more likely to occur in children with systemic diseases, owing to local and systemic predisposing factors (immunodeficiencies, diabetes mellitus, endocrine disturbances, antibiotic and corticosteroid therapies, xerostomia and poor oral hygiene). In general it is most common in early and later stages of life. All three cases in the present study belonged to age group of 0-5 years. Two of them were infants who might be using pacifiers and one of them was hospitalized and was on antibiotic therapy.

Gingival hyperplasia

Gingival hyperplasia was reported in three cases (2.5%). Gingival hyperplasia can occur due to variety of causes as in chronic gingivitis, due to use of some drugs, puberty induced etc. All the cases in the present study belonged to age 13-18 years and two out of three cases were females.

Verruca vulgaris

Verruca vulgaris or a common wart is a benign skin lesion caused by a specific human papilloma virus (HPV 2and 4). The oral lesions may be single or multiple and are frequently located on lips, palate and rarely on other oral regions. Verruca vulgaris was seen in a single patient (0.83%). Various authors have shown very low prevalence, Garcia Pola (0.29%) in Spain, Arendroff TM (0.2%) in South Africa, Kleinman DV(0.03%) in United States[21]. The lesion found in present study was present on and around lips and was unilateral and multiple in presentation.

Smokeless tobacco associated lesion

Smokeless tobacco associated lesion was observed in a single case forming 0.83% of total lesions. Klienman DV et al[1] has studied prevalence of tobacco associated lesions in children and adolescents in US and he found 0.71% prevalence of the same. It was one of the four most common lesions found. It is common to start tobacco chewing or smoking in adolescence, which shows the consequences in the form of mucosal alterations after some years. In studies by Mathew et al and Sudhakar S et al[26] showed that the number of tobacco associated lesions increased with increasing age.

Other miscellaneous Lesions

Although listed in the proforma was no case of ANUG seen in the present study. Kleinman DV et al[1] found a prevalence of 0.1% in U.S and Sheiham A reported a prevalence of 11.5 % in Nigerian children. Lesions found in category ‘other’ were nine cases of melanin pigmentation, five cases of oral lichen planus, three cases of fissured tongue, one case of median rhomboid glossitis, one case of hairy tongue, one case of exfoliative cheilitis and one case of operculum.

Ten cases were categorized under ‘unknown’ meaning they could not be diagnosed as a specific lesion according to the diagnostic criteria or by the researcher. They were present on tongue, palate, lips and floor of mouth in decreasing order. Six out of ten were unilateral and mostly all were present on a single site and all ten cases were asymptomatic.

One of the objectives of present study was to look for any associated skin disorders with oral mucosal lesions. 12 cases out of total 120 patients (10%) had an associated skin disorder. The associated skin disorders were Lichen planus, Psoriasis, Rashes, Herpes simplex, Steven Johnson syndrome, Verruca vulgaris, Epidermolysis bullosa.

Since there is limited literature on oral mucosal pathology in children and adolescents, there were few studies with which the present study could be compared. This area is one of the most important aspects of oral health but it has been ignored to a greater extent so far despite of the recommendations by WHO to conduct more epidemiological studies on this topic.

The present study was done on patients visiting hospitals and not the community as a whole. About 75% of cases of lesions in the present study were self reported which means the lesion was the cause for the visit of the patient. So the chances of missing asymptomatic lesions or lesions with mild symptoms for which people do not take professional advice also had to be accounted for.

Conclusion

Results of the present study showed a relatively higher prevalence of oral lesions in children and adolescents which requires attention. Thus it is imperative that complete careful examination be carried out for each and every patient as cursory examination may miss out the important findings. Further more studies are required for oral lesions prevalence in larger sample in a community based set up as there are many asymptomatic lesions for which an individual never seeks professional advice or visits the hospital with an adoption of universal diagnostic criteria so that variation in overall lesion prevalence could be minimized.

References

1. Cebeci AR I, Gulsahi A, Kamburoglu K, Orhan BK, Ozta#1; B. Prevalence and distribution of oral mucosal lesions in an adult turkish population. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2009 Jun 1;14 (6):E272-7

2. Majorana A, Bardellini E, Flocchini P, Amadori F, Conti G, Campus G. Oral mucosal lesions in children from 0 to 12 years old: ten years' experience.Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2010 Jul;110(1):e8-13.

3. Parlak AH, Koybasi S, Yavuz T, Yesildal N, Anul H, Aydogan I,Cetinkaya R, Kavak A. Prevalence of oral lesions in 13- to 16-year-old students in Duzce, Turkey. Oral Dis 2006;12:553-8.

4. Crivelli MR, Aguas S, Adler I, Quarracino C, Bazergue P. Influence of socio-economic status on oral mucosa lesion prevalence in schoolchildren. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1988; 16: 58-60.

5. Kleinman DV, Swango PA, Pindborg JJ. Epidemiology of oral mucosal lesions in United States schoolchildren: 1986-87. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1994; 22: 243-53.

6. Redman RS. Prevalence of geographic tongue, fissured tongue, median rhomboid glossitis and hairy tongue among 3,611 Minnesota schoolchildren. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1970; 30: 390-5

7. Shulman J D. Prevalence of oral mucosal lesions in children and youths in the USA. Intl J Paediatr Dent 2005; 15(2):89-97.

8. Sudhakar S,Praveen Kumar B, Prabhat MPV. Prevalence Of Oral Mucosal Changes in Eluru, Andhra Pradesh (India)- An Institutuinal Study. J Oral Health Comm Dent 2011;5(1):42-6

9. Bessa CFN, Santos PJB, Aguiar MCF, do Carmo MAV. Prevalenceof oral mucosal alterations in children from 0 to 12 yearsold. J Oral Pathol Med 2004; 33:7-22.

10. Bezerra S, Izabel C. Oral conditions in children from birth to 5 years: the findings of a children's dental program. J Clin PediatrDent2008; 25(1):79-81

11. Arendorf TM, Van der Ross R. Oral lesions in a black pre-school South African population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1996; 24: 296-97.

12. Garcia-Pola MJ, Garcia-Martin JM, Gonzalez-Garcia M. Prevalence of oral lesions in the 6-year-old pediatric population of Oviedo (Spain). Med Oral 2002;7:184-91

13. Rioboo Crespo MR, Planells del Pozo P, Rioboo Garcìa R.Epidemiology of the most common oral diseases in children. Med Oral Patol Cir Bucal 2005; 10:376-87.

14. College C, Feigal R, Wandera A, Strange M. Bilateral versus unilateral mandibular block anesthesia in a pediatric population.Pediatr Dent 2000 Nov-Dec; 22 (6):453-7.

15. Ata-Ali J , Carrillo C , Bonet C , BalaguerJ, Peñarrocha M , Penarrocha M; Oral Mucocele: Review Of The Literature.J Clin Exp Dent 2010;2(1):e10-3.

|