Introduction

Replacement of a missing tooth involves different therapeutic options in dentistry. However, when it comes to young children and adolescents, the treatment options differ. For replacement of a missing tooth, implants are the treatment of choice but their use in not intended until the end of growth period. Another option is of removable partial denture which is the most easily fabricated and cheapest option but they are unacceptable to many patients because of their bulkiness, frequent fractures and unaesthetic appearance.[1]

Other options include a fixed partial denture which requires tooth reduction. Reduction in a tooth with large pulp chamber in an adolescent can lead to hypersensitivity or pulpal damage. So a technique with minimum preparation is the treatment of choice in young patients. One such technique is the use of resin bonded bridges (RBB).

Resin bonded bridges (RBBs) are minimally invasive fixed prostheses which rely on composite resin for retention. These restorations were first described in the 1970s. The first type of RBB was the Rochette Bridge, which relied on the retention generated by resin cement tags through a perforated metal retainer.[2]

Another such technique of replacing a missing tooth is Maryland Bridge. This bridge technique was first developed at the University of Maryland. [3],[4]

These resin bonded bridges (RBB) were electrochemically etched and exhibited much superior retention then Rochette Bridge.

The main advantage of RBBs is that, in comparison to conventional bridge preparations, they are conservative of tooth structure.[5] By using a RBB it is possible to provide a fixed replacement for missing teeth which is essentially reversible and does not com¬promise the abutment tooth.

This article describes two clinical cases of replacement of tooth in adolescents in both anterior and posterior region using a new technique of resin bonded bridge.

Case Report 1

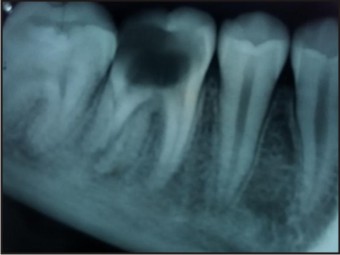

A 14 year old male patient reported to Department of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry with chief complaint of pain in lower right back tooth region. On examination 46 was grossly carious. Radiographic examination revealed furcation involvement and large periapical pathology (Figure 1). Endodontic treatment and restoration was not possible due to poor prognosis, hence it was extracted after patient’s consent. Patient was recalled after 2 weeks for further treatment (Figure 2). Since the patient was not willing to wear a removable appliance, a fixed appliance was fabricated as an affordable interim alternative. This bridge was intended to remain in place until the patient’s growth period was complete and was ready to receive an implant.

| Figure 1 : Intra Oral Periapical Radiograph W.R.T #46

|

| Figure 2 : Photograph Showing Edentulous Span W.R.T #46

|

Technique

Alginate impressions of both the arches were taken. The working model was made in dental stone. A 26R09; G stainless steel orthodontic wire was used to create a mesh corresponding to the edentulous space (Figure 3). The length and contour of mesh corresponded to the edentulous space and the gingival contour. The width of mesh was less than the buccolingual width of the crown. The ends of the mesh wire were extended onto the buccal and lingual surfaces of mandibular second permanent molar and second premolar. The gingival extension of the wire mesh was placed 1 mm above the ridge to allow adequate cleansing, prevent food entrapment or gingival irritation. A mandibular first molar resin tooth was selected as pontic. The pontic had a smaller occlusal table to minimize masticatory stresses. It was attached to the finished wire framework using clear auto polymer acrylic resin, matching the shade of the pontic (Figure 4). The acrylic attachment was finished and polished. The bridge was ready for a try in, in the patient’s mouth for final adjustments. The bridge was assessed for the gingival extension and soft tissue blanching. The occlusal and eccentric movements were adjusted. The ends of the mesh wire were bonded onto the second molar and second premolar with composite resin after adequate etching and bonding (Figure 5, 6).

| Figure 3 : Wire Meshwork Fabricated On Model

|

| Figure 4 : Lateral View Of Pontic Design

|

| Figure 5 : Post Operative Occlusal View

|

| Figure 6 : Lateral View In Occlusion

|

Case Report 2

A 9 year old male patient reported to the department with an edentulous span in relation to #21, having lost that tooth 3 months back secondary to a sports injury (Figure 7). There was no space loss in the anterior region and Class 1 molar occlusion was present. Slight midline shift could be seen. It was explained to the patient and parents that the ideal treatment would be an implant supported prosthesis after the growth of the jaws was complete. Meanwhile, an interim restoration was planned, which would be a resin bonded prosthesis so as to cause no or minimal preparation of the adjacent permanent teeth.

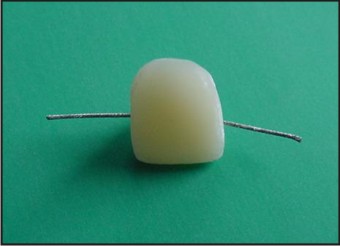

After the impressions were taken and the models were made, an acrylic tooth of the nearest color and size was chosen and adjusted according to the span. Its palatal surface was reduced. A 19 gauge wire was adapted from the distal of #11 till the distal of #21. Serrations were made throughout its length and it was sandblasted. Then it was imbibed in the acrylic tooth palatally using tooth colored acrylic resin (Figure 8). Occlusal and gingival adjustments were made and then the prosthesis was bonded to the abutments with composite resin. This gave direct resin bonded prosthesis without compromising the adjacent young permanent teeth (Figure 9). The patient was evaluated after 1, 3 and 6 months and is still under observation.

| Figure 7 : Pre Operative Photograph Showing Missing #21

|

| Figure 8 : Prosthesis Design

|

| Figure 9 : Post Operative Photograph

|

Discussion

In today’s dental practice a missing tooth in the anterior region of mouth is not only a physical loss but also a psychological trauma for the patient.

Ideally, as the occlusion develops from the primary dentition to the permanent dentition, a sequence of events occurs in an orderly and timely fashion. Loss of teeth in posterior region of mouth can disrupt this sequence and may affect the occlusal status of the permanent dentition.

Loss of permanent teeth in children may require measures like passive space maintenance to restore the normal process of occlusal development and maintain space for future treatment options like implants. Many treatment modalities are available for replacing a single missing tooth such as removable partial denture, fixed partial denture, autotransplantation of third molar or dental implant but each modality has its own advantages and disadvantages.

The traditional treatment for a single edentulous space is a conventional fixed partial denture. Large pulp chambers in the abutments, expected transition in the position of the gingiva and the age of patient were factors that were considered and the use of conventional fixed prosthesis was rejected in this case.

RBBs were preferred over Rochette bridges because the wings had reduced thickness and provided adequate retention with minimal preparation. If needed, chairside repair could be easily done in case of wear of composites.

A cantilever resin retained bridge was not preferred in both the cases as the retention would have been compromised.

Resin bonded bridge was considered ideal because of its conservative nature that would allow tooth and soft tissues to mature before a more conventional and definitive restoration be fabricated.[6],[7] RBBs can also be used to replace single posterior tooth where healthy abutments can be saved from excessive reduction. RBBs have the advantages of taking minimal clinical time[8] and rarely requiring anaesthetic, therefore they may be appro¬priate for patients who are apprehensive of dental treatment. RBBs can now be considered to be a minimally invasive, relatively reversible, aesthetic and predictable restoration for prescription in general dental practice.

The bridges given were functional, readily acceptable by the patient, maintained the mesiodistal diameter of the lost tooth, prevented supra eruption of opposing teeth and did not restrict normal growth and development.[9] It is easy to construct, needs a short fabrication time and the materials are easily available. It involved simple fabrication technique, hence could be completed in a single appointment. The appliance is easy to clean and maintain. Hygiene is easily maintained with no food entrapment.

Three most common complications, however, associated with resin bonded prosthesis are debonding (21%), discoloration (18%) and caries (7%).[10] To prevent these complications oral health education, encompassing oral hygiene instruction and advice regarding diet and the use of fluoride, should be provided.

Conclusion

Resin bonded bridges represent a minimally invasive, cost effective, time saving and long lasting treatment modality. Resin bonded bridge’s may be proposed as a suitable treatment modality especially in patients who do not want removable options for replacement of early loss of permanent teeth. In this case, the noninvasive characteristic of this treatment renders it superior to all other options for its use both in anterior as well as posterior regions.

References

1. Holt LR, Drake B. The Procera Maryland bridge. A case report. J Esthet Restor Dent 2008;20(3):165-71.

2. Howe D F, Denehy G E. Anterior fixed partial den¬tures utilizing the acid-etch technique and a cast metal framework. J Prosthet Dent 1977; 37: 28–31.

3. Terry Donovan DDS, The procera maryland bridge: a case report , Journal of esthetic and restorative dentistry : volume 20 : 3 , 172-3.

4. Sabita M. Ram, Deshpande P, Rubina. The zirconia resin bonded prosthesis: A case report. Dental practice. 2010; 9(2): 12-14.

5. Edelhoff D, Sorensen J A. Tooth structure removal associated with various preparation designs for anterior teeth. J Prosthet Dent 2002; 87: 503–509.

6. Shilingburg HT, Hobo, S: Fundamentals of fixed prosthodontics, 3rd edition, Quintessence Publishing Co Inc, IL, 1997,pg 85.

7. Shilingburg HT, Hobo, S: Fundamentals of fixed prosthodontics, 3rd edition, Quintessence Publishing Co Inc, IL, 1997,pg 537.

8. Verzijden C W, Creugers N H, van’t Hof M A. Treatment times for posterior resin-bonded bridges. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1990; 18: 304–308.

9. Graber TM. Orthodontics: Principles and Practice. Philadephia W.B.: Saunders and Co; 1992. p. 640R09;1.

10. Goodacre CJ, Bernal G, Rungcharassaeng K, Kan JY,. Clinical complications in fixed prosthodontics. J Prosthet Dent Jul 2003;90(1):31-41.

|