Introduction

Gingival recession is the most common and undesirable condition of the gingiva and its prevalence increases with age. It is characterized by displacement of gingival margin apically from cemento-enamel junction (CEJ) and exposure of root surface to the oral environment[1]. Gingival recession is defined as location of marginal periodontal tissues apical to cemento-enamel junction[2]. It can be localized or generalized and often is associated with one or more surfaces[1]. Gingival recession, often a source of anxiety to patients and perplexity to those treating them, is an intriguing and complex phenomenon[4]. Although many dental conditions pass by patients unnoticed, gingival recession can often be a visible dental change that is noted by patients and which may cause them to seek advice of a dentist. The prevalence of this condition is high, but in some patients, recession may be sign of periodontal disease. Therefore, prevention and control of gingival recession is based on an accurate survey of the prevalence of the condition in relation to the risk factors that contribute to its development[5]. Recession may exist in the presence of normal sulci and undiseased interdental crestal bone levels or may occur as the part of the pathogenesis of the periodontal disease where alveolar bone is lost[6]. The etiology of gingival recession is multifactorial. Several factors may play a role in recession development, such as excessive or inadequate tooth brushing, destructive periodontal disease, tooth malpositioning, alveolar bone dehiscence, thin marginal tissue covering a non-vascularized root surface, high muscle attachment, frenal pull and occlusal trauma. Other causative factors that have been reported are iatrogenic factors related to reconstructive, conservative, periodontologic, orthodontic or prosthetics treatment[7]. Despite common observation in adults; the prevalence, extension and degree of severity of gingival recession present considerable differences among various study populations. Prevalence indicates number of cases or occurrences of gingival recession; extension corresponds to the number of teeth affected by gingival recession; and severity signifies the total root surface exposed by the gingival recession, i.e. the linear apico-coronal height of the gingival recession[8]. The concern on these alterations is based on the potential consequences they may bring about, which affect not only oral health but also the general health. Following gingival recession, several complications like pain, tooth loss, loss of esthetic appearance, plaque retention, root caries and tooth abrasion may occur[9]. In addition to all clinical implications associated with the presence of gingival recession, such alterations have been regarded as the clinical manifestation of the periodontal attachment loss and may be an important aspect in the diagnosis of susceptibility to periodontal disease. Thus, perception of the occurrence of gingival recession in a given population is a basic need for their prevention and control and allows the proper planning of health centers based on information on the prevalence and severity of these lesions, in order to establish proper and effective preventive programs that may control the onset and/or progression of gingival recession, as well as to avoid the complex local disturbances that may develop[10]. Several epidemiological studies on prevalence and severity of gingival recession have been conducted in Western population. Therefore, the present study was carried out to evaluate prevalence, severity and extension of gingival recession in local adult population sample of Sunam, Punjab.

Materials And Methods

The study population of the present study comprised of 200 patients aged above 18 years who sought dental treatment at Guru Nanak Dev Dental College and Research Institute, Sunam, Punjab. All participants were informed about the evaluation to which they would be submitted. The subjects of both genders were divided in 4 groups according to the age range: Group I : 18 to 29 years: 50 patients; Group II : 30 to 39 years: 50 patients; Group III : 40 to 49 years: 50 patients; Group IV : >50 years: 50 patients. The selection criteria comprised a mean number of 20 natural teeth, since large numbers of missing teeth might interfere with the results of this study. The participants of the present study were evaluated by a single examiner, who was not submitted to any previous calibration.

Exclusion Criteria

Third molars were excluded from the study. Patients with systemic disease and smokers were also excluded.

Method

A millimetered periodontal probe marked up to 15 mm, UNC-15, Hu-Friedy, was employed for evaluation of the teeth of each subject by a single examiner, concerning the presence of gingival recession, which was recorded whenever there was more than 1 mm of root surface exposed. Two surfaces were evaluated in each tooth: buccal and lingual, and linear measurements were obtained from the cementoenamel junction up to the gingival margin in the teeth presenting with gingival recession, in order to evaluate the vertical (apicocoronal) width of the recession.

Vertical Component

Linear measurements were obtained from the cementoenamel junction upto the gingival margin in the teeth presenting with gingival recession. In cases where the cementoenamel junction was covered by calculus, hidden by a restoration or lost due to caries or wear lesions, the location of such junction was estimated on the basis of the adjacent teeth, similar to a previously used methodology. Three categories were established according to apico-occlusal dimension of the root surface exposed by gingival recession; mild recessions: less than 3 mm of root surface exposed; moderate recessions: 3 to 4 mm of root surface exposed; advanced recessions: more than 4 mm of root surface exposed to the oral environment. Gingival recession was recorded according to P.D Miller’s classification of marginal tissue recession[11].

Horizontal Component

Measurement was taken as proportion of root exposed at the level of cementoenamel junction. The criteria for scoring of horizontal component was as follows:

• Score 0 : no clinical evidence of root exposure

• Score 1 : exposure upto 10%

• Score 2 : exposure >10% but not exceeding 25%

• Score 3 : exposure > 25% but not exceeding 50%

• Score 4 : exposure > 50% but not exceeding 75%

• Score 5 : exposure > 75% upto 100%

Statistical Analysis

The recorded data was compiled and subjected to statistical analysis using Chi-Square test. Normality of quantitative data was checked by measures of Kolmogorov Smirnov tests of normality. A p- value of < 0.0001 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All calculations were performed using SPSS® version 17 (Statistical Packages for the Social Sciences, Chicago, IL).

Results

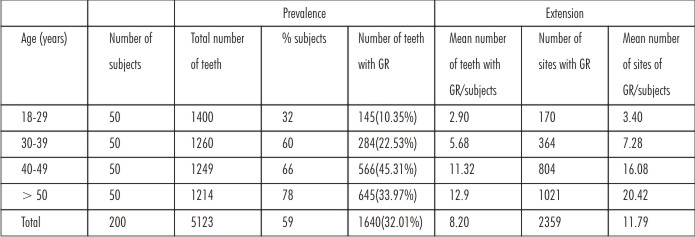

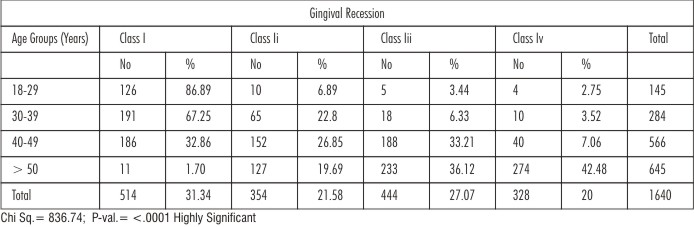

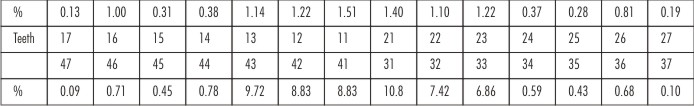

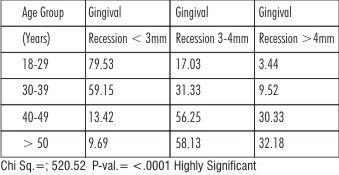

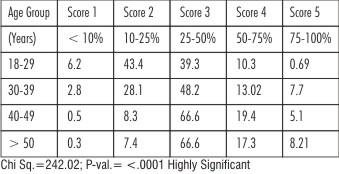

The study revealed gingival recession in 118 subjects out of 200, which is 59% of the total sample examined. Among 5123 teeth of the 200 subjects examined; 1640 teeth displayed gingival recession corresponding to 32.01% of the total teeth examined. Among all the subjects, mean number of teeth with gingival recession was 8.20 and gingival recession was observed in 2359 sites with the mean number of sites of gingival recession per subject as 11.79 (Table I). Results show that the prevalence of gingival recession increased significantly with age. Among the study sample, the prevalence of gingival recession increased from 32% in age group of 18-29 years to 60% in 30-39 years, 66% in 40-49 years and 78% in age group > 50 years. Increase in age also led to increase in the mean number of teeth with gingival recession. Similarly the extension of gingival recession was also found to be increased with age. The mean number of teeth with gingival recession per subject at 18-29 years age group (2.90) was significantly less than at the age groups above 50 years (12.9) (Table I). The results also show that there was a significant difference in distribution of Miller classes and the age groups. In age groups 18-29 and 30-39 years, Class I gingival recession was more prevalent i.e 86.89% and 67.25% respectively whereas Class III and Class IV gingival recessions were more prevalent in older age groups (Table II). Only 2.75% of subjects of age groups 18-29 years had Class IV gingival recession as compared to 42.48% at the age groups above 50 years; at the older age groups more than 50 years; Class III and Class IV gingival recessions were 36.12% and 42.48% respectively, whereas only 19.69% subjects had Class II gingival recession and 1.70% subjects had Class I gingival recession (Table II). Mandibular anterior teeth i.e central incisors, lateral incisors and canines revealed more gingival recession as compared to rest of the teeth (Table III). It was noted that the gingival recession (based on apico-coronal height of recession) increased with age. Only 3.44% of teeth were affected by severe form of gingival recession (> 4 mm) at the age group of 18-29 years as compared to 32.18% at the age groups above 50 years (Table IV). 43.4% of teeth at age group of 18-29 years showed horizontal recession extending from 10-25% whereas with increasing age i.e in age group of 40- 49 years and above 50 years, horizontal recession of 25-50% was seen in 66.6% teeth (Table V). All these results clearly indicate that the prevalence, extension and severity of gingival recession increased with increasing age.

| Table I: Prevalence And Extension Of Gingival Recession According To Age Group

|

| Table II: Scoring Of Severity Of Gingival Recession According To P.D. Miller Criteria 1985

|

| Table III: Intraoral Distribution Of Gingival Recession

|

| Table IV: Percentage Severity Of Gingival Recession According To Age Groups (Vertical Dimension)

|

| Table V: Percentage Severity Of Gingival Recession According To Age Groups (Horizontal Dimension)

|

Discussion

Several epidemiological studies reveal important information on prevalence and severity of gingival recession and can be used to predict the disease pattern, progression and treatment needs etc. In the present study, the overall prevalence of gingival recession was found to be 59%. Significant association was found between gingival recession and age. It was observed that severity of gingival recession increased with age. Least prevalence was seen in Group I with age 18-29 years (32%) and highest prevalence was seen in Group IV with age > 50 years (78%). The reason could be related to poor oral hygiene among the participants; population being rural. This negligence of oral hygiene thus tends to increase the pocket depth and loss of attachment. Gorman WG (1967) and Murray JJ (1973) also reported similar findings[12],[13]. The relationship between increased prevalence of gingival recession and age may probably be because of the longer period of exposure to agents that cause gingival recession, associated to intrinsic changes in the organism, both local and systemic, besides the cumulative effects of the lesion itself[10]. Gingival recession in young patients is usually localized, which seems to be the result of isolated etiological factors. As the age increases, gingival recession becomes more generalized in distribution (prevalence, extension and severity increases) which may be due to cumulative effect of local factors. The main precipitating factors of gingival recession are bacterial plaque, mechanical trauma related to the employment of hard-bristled toothbrushes, brushing technique and frequency of toothbrushing, orthodontic therapy and chemical trauma, primarily related to smoking. Other factors that favour the occurrence of gingival recession are functionally unsatisfactory quantity and quality of attached gingiva, bone dehiscence, buccal tipping, high frenum attachment and traumatic occlusion[10]. In the present study, gingival recession was found to be more prevalent in the mandibular anterior teeth. Similar results were seen in the studies performed by Vehkalathi M et al 1989, Guimaraes MG and Aguiar EG 2012, Humagain M and Kafle D 2013 and Anarthe R et al 2013[14],[15],[8],[1].

Maxillary teeth were found to be less frequently affected by gingival recession (1.5%) which may be related to the characteristics of keratinized mucosa, which is wider and thicker in maxilla than in the mandible[8]. Areas with deficient keratinized mucosa, especially as regards thickness, have been demonstrated to be more susceptible to gingival recession, especially due to smaller amount of connective tissue available in the area, that leads to localized inflammatory reactions triggered by different processes to be able to affect the entire extension of the tissue, ultimately leading to gingival recession[10]. However, studies by Gorman WJ et al in 1967 and Chrysanthakopoulos NA in 2010 showed a higher prevalence of recession in maxillary teeth which maybe due to faulty toothbrushing or due to thin or absent bone plates[12],[16]. Checchi L et al in 1999 found that in the age group of 19-25 years old, canines of both jaws were the teeth most frequently affected by gingival recession[17]. Murray JJ in 2006 showed that the most frequently affected teeth were mandibular incisors followed by first maxillary molars, first mandibular molars, premolars of both jaws, second maxillary molars, second mandibular molars and canines of the mandible[13]. As regards the teeth most frequently affected by gingival recession, no agreement is observed in literature. Watson PJC in 1984 indicated the maxillary canines and premolars to be most affected as they have a prominent position in jaw[18]. No significant differences were observed in the occurrence of gingival recession at the right and left sides which is in agreement with the findings of Vehkalathi M (2011) and Anarthe R et al (2013)[14],[1]. In our study, Miller’s Class I recession was the most prevalent in Group I (86.89%) whereas Class III and Class IV recessions were more prevalent in Group IV (36.12% and 42.48%). In agreement to the findings of other epidemiological studies, the present study also yields the finding that the prevalence, extension and severity of gingival recession increases with age.

Conclusion

Gingival recession is most commonly occurring periodontal condition. It mainly occurs due to faulty oral hygiene practices by the patients, it causes alarming conditions like tooth sensitivity, food lodgment, plaque retention and esthetic problems. The prevalence of gingival recession was found out to be 59% in the local population of Sunam, Punjab. In subjects below 40 years of the age class I and class II gingival recessions were more prevalent whereas in those above 40 years, class III and class IV gingival recessions were more prevalent. The mandibular anterior teeth were the most affected teeth with gingival recession. There is necessity to do the longitudinal studies for exact assessment of prevalence, extension and severity gingival recession. Present study is conducted to assess gingival recession in the rural population so that dental practitioners and dental hygienist should take more efforts to educate the patients regarding oral hygiene practices for the prevention of such conditions in periodontium and if the condition has started, it should be treated immediately to avoid the further complications.

References

1. Anarthe R, Mani A, Marawar PP. Study to Evaluate Prevalence, Severity and Extension of Gingival Recession in the Adult Population of Ahmednagar District of Maharashtra State in India. IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences Volume 6, Issue 1 (Mar.- Apr. 2013), PP 32-37.

2. Glossary Of Periodontal Terms, 4th edition.

3. Amran AG, Ataa MAS. Statistical analysis of the prevalence, severity and some possible etiologic factors of gingival recessions among the adult population of Thamar city, Yemen. RSBO. 2011 July-Sept;8(3):305-13.

4. Smith RG. Gingival recession. Reappraisal of an enigmatic condition and a new index for monitoring. J Clin Periodontol 1997; 24: 201-205.

5. Toker H, Ozdemir H. Gingival recession: epidemiology and risk indicators in a university dental hospital in turkey. Int J Dent Hygiene 2009;7:115-120

6. Tugnait A, Clerehugh V. Gingival recession-its significance and management. Journal of Dentistry 2001;29:381-394.

7. Chrysanthakopoulos NA. Occurrence, Extension and Severity of the Gingival Recession in a Greek Adult Population Sample. J Periodontol Implant Dent 2010; 2(1): 37-4.

8. Humagain M, Kafle D. The Evaluation of Prevalence, Extension and Severity of Gingival Recession among Rural Nepalese Adults. Orthodontic Journal of Nepal, Vol. 3, No. 1, June 2013.

9. Lafzi A, Abolfazli N, Eskandari A. Assessment of the Etiologic Factors of Gingival Recession in a Group of Patients in Northwest Iran. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospect 2009; 3(3):90-93.

10. Marini MG, Greghi SLA, Passanezi E, Santana ACP. Gingival recession: prevalence, extension and severity in adults. J Appl Oral Sci 2004; 12(3): 250-5.

11. Miller PD. A classification of marginal tissue recession. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 1985; 5(2):8-13.

12. Gorman WJ. Prevalence and etiology of gingival recession. J Periodontol 1967; Jul/ Aug; 38(4): 316-22.

13. Murray JJ. Gingival recession in tooth types in high fluoride and low fluoride areas. J Periodontol 1973;8:243-251.

14. Vehkalahti M. Occurrence of gingival recession in adults. J Periodontol 1989;60:599-603.

15. Guimaraes GM, Aguiar EG. Prevalence and type of gingival recession in adults in the city of Divinopolis, MG, Brazil. Braz J Oral Sci 2012;July-September;11(3).

16. Chrysanthakopoulos NA. Aetiology and Severity of Gingival Recession in an Adult Population Sample in Greece. Dent Res J 2011; 8(2): 64-70.

17. Cheechi L, Daprile G, Gatto MRA, Pelliccioni GA. Gingival recession and toothbrushing in an Italian school of dentistry: a pilot study. J Clin Periodontol 1999;26:276-280.

18. Watson PJC. Gingival recession. Journal of Dentistry 1984;12(1):29-35.

|