Introduction

Fracture of the mandibular condyle is fairly common and account for 25% to 35% of all mandibular fractures.The treatment of condylar fractures has always been a controversial issue among the surgeons. Robert V. Walker (1994)[1] stated thatadequately restored function of the jaw after fracture of the condyle consists of five determinable features: 1) pain free mouth opening with an inter incisal distance beyond 40 mm; 2) good movement of the jaw in all excursions; 3) pre injury occlusion of the teeth; 4) stable temporomandibular joints; and 5) good facial and jaw symmetry. If these criteria are met, it matters a little how fractures of the mandibular condyle are managed. Closed as well as open reduction have associated complications including deviation of the chin and facial asymmetry, reduced mandibular mobility, dysfunction of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), ankylosis, chronic pain and malocclusion.[2]

For the present time the key question remains, “What are ‘THE’ indications for selecting from the range of treatment available for condylar injuries?”

As there is no protocol governing the treatment of condylar fractures, the aim of this paper is to review the pertinent literature and propose guidelines for treatment.

Indications for open reduction of mandibular condyle fractures

The various condylar fracture classifications of Brophy, Thoma, Rowe and Killey and Dingman and Natvig relied on anatomic findings usually found on radiography, not the functional assessment of the patient.[3] These anatomic classifications are of little contemporary clinical value.

It is important when considering a particular intervention or management strategy that similar problemsare being addressed under similar circumstances. This suggests that a uniform classification scheme or system of terminology and similar indications for therapy should exist. Unfortunately, when dealing with mandibular condyle injuries, a multitude of classification schemes and considerations for indications exist.

Archer (1975) tried to summarize that there is no indication for the open reduction of subcondylar fractures as surgery in the form of open reduction frequently results in trismus or ankylosis, or sterile or suppurative resorption of the condyle.

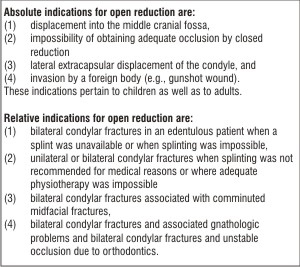

Zide and Kent (1983)[4] attempted to outline the indications for open reduction. (Table 1)

| Table 1

|

However, they did so in an era before stable fixation (followed by immediate function) of these fractures could be obtained. With the initial application of rigid internal fixation techniques to the craniomaxillofacial skeleton in the mid-1980s, new indications and contraindications have slowly evolved.

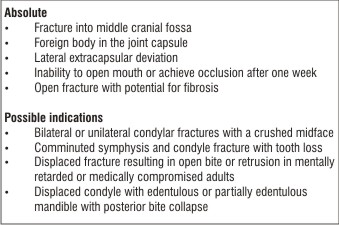

The slow transition observed as the absolute, relative and possible indications by Zide’s 1989[5] evolved over a period of time (Table 2).

| Table 2

|

Kent et al (1990)[6] indications for open Reduction are:

(1) Displacement into middle cranial fossa

(2) Tympanic plate injury

(3) Impossibility of obtaining adequate occlusion

(4) Lateral extracapsular displacement

(5) Invasion by foreign body

(6) Failure to obtain segment contact because of intervening soft tissue

(7) Blocked mandibular opening

(8) Facial nerve paresis secondary to initial injury

(9) Contraindicated intermaxillary fixation

(10) Open wounds from initial injury Several authors have suggested surgical therapy in cases of unilateral fractures in adults, when the dislocation is more than 45o to the ramus axis in a frontal view or when the condylar head is dislocated from the glenoid fossa.[7]

Matthew B. Hall (1994)[8] proposed few more relative indications in addition to Zide’s list :

Significantly displaced and dislocated condyles in teenagers and adults, when the goal is rigid internal fixation and immediate function in order to minimize any possible adverse sequelae and return the patient as rapidly as possible to normal activities.

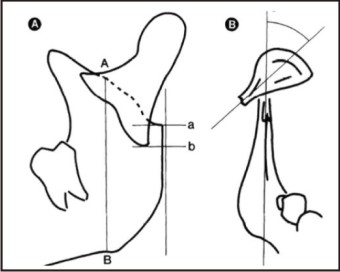

Nils Worsaae et al. (1994)[9] suggested radiographic calculation of the vertical overlap of fragments at the posterior border of the mandibular ramus/condylar process in millimeters and calculated it in percent of the ramus height on the panoramic radiographs , registered as the distance between the sigmoid notch and the base of the mandible parallel to the posterior border. On the posteroanterior radiographs the medial or lateral angulation between the dislocated condyle and ramus was measured. (Fig 1)

| Figure 1

|

No correlation between the degree of radiographically recorded dislocation or angulation of the condylar fragment and the number of complications was observed. However, it has to be emphasized that the analysis in this study was performed on non-standardized radiographs.

Widmark et al (1996)[7] indicated surgical treatment whenthe dislocation is greater than 30o withrespect to the longitudinal axis, in bothlateral and frontal projections, or whenshortening of the ramus of at least 5 mm(as seen radiographically) accompaniesthe dislocation.

Peter Banks (1998)[10] addressed both the treatment modalities for condylar fractures and suggested:

Conservative treatment in children before puberty

Operative intervention when loss of vertical ramus height cannot be compensated in any other way particularly in the bilateral condylar fractures.

Ulrich Joos, Johannes Klelnheinz (1998)[11] showed that the choice of treatment should be based on objective measurable quantitative condylar changes i.e. level of fracture line, degree of dislocation and extent of loss of height. They elaborated the following differential concept of treatment. (Table 3)

| Table 3

|

Jelle Hovinga et al. (1999)[12] concluded that non-surgical management of unilateral and bilateral fractures of the mandibular condyle in children is the method of choice. Primary surgical management should only be considered in selected cases involving extensive dislocation with lack of contact between the bone fragments, dislocation of the condyle in the mid-cranial fossa and in cases with multiple fractures of the midface, in which the mandible has to serve as a guide to reposition the midfacial bones.

Undt et al (1999)[13] considered indications for open intervention to be

a medial tilt of the condylar fragment of more than 14°,

shortening of the ramus by more than 5%,

insufficient contact of fragment, minor dislocation, and/or

when other fracture require general anesthesia to avoid maxillomandibular fixation.

American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Special Committee on Trauma listed indications for open reduction of condylar fractures in 2001.[14]

Physical evidence of fracture

Imaging evidence of fracture

Malocclusion

Mandibular dysfunction

Abnormal relationship of jaw

Presence of foreign bodies

Lacerations and/or hemorrhage in external auditory canal

Hemotympanum

Cerebrospinal fluid otorrhea

Effusion

Hemarthrosis

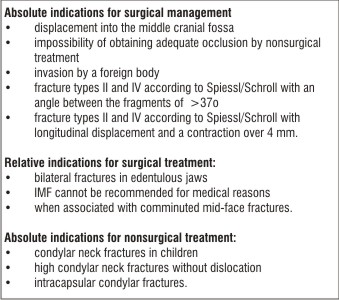

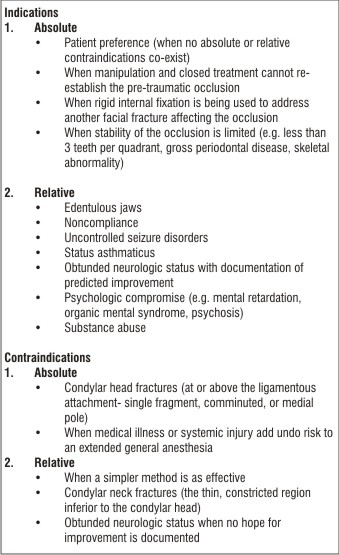

Richard H. Haug and Leon A. Assael (2001)[23] developed a protocol for the treatment of condylar process fractures that included absolute and relative indications and contraindications to open reduction. (Table 4).

| Table 4

|

Leon A. Assael (2003)[3] concludedthat theclinical decision regarding the need for surgery must be made after assessing the variables affecting condylar fracture treatment selection and outcome. These variables are patient age, gender, systemic diseases, patient compliance, risk of infection, risk of nerve injury, risk for scarring, risk for chronic pain, comminution, hemarthrosis, disc injury, osteoarthrosis and bone resorption, associated mandible fractures, associated midface fractures, associated cranial base fracture, edentulism (partial or full), dentofacial Angle’s class II classification, other dental function and occlusion considerations, location of condylar fracture (low, medium, high) and displacement of proximal (condylar) segment, clenching and bruxism, functionally shortened ramus, patient expectations, ability of the surgeon, technology of the health care environment, institutional resources, willing payer.

According to Nicholas Zachariades et al. (2006)[15] open versus closed treatment is judged individually. He proposed that

Even if significant displacement of the fracture is present, the treatment should be non-surgical as long as the condyle is in the fossa.

Unilateral condylar fractures, fractures with normal occlusion and the majority of non-displaced or slightly displaced condylar fractures are best treated non-surgically.

Displaced condylar fractures with altered occlusion may also be treated satisfactorily in 50% with intermaxillary fixation.

Absolute indications for non-surgical treatment are intracapsular condylar fractures, high condylar fractures close to or involving the articular surface and fractures in growing children.

Conservative treatment may be required when the patient’s past medical history does not allow the administration of general anaesthesia.

Surgery should be performed in cases of severely displaced condyles i.e. displacement greater than 45o in either the coronal or the sagittal plane and lateral extracapsular displacement.

Medial or lateral override resulting in significant loss of vertical ramus height that cannot be compensated in any other way is an indication for open reduction.

Open reduction is recommended for condylar fractures associated with fracture(s) elsewhere in the mandible and as part of a panfacial injury and/or comminuted maxillary fractures.

Open reduction is recommended when it is impossible to achieve pretraumatic or adequate occlusion by closed reduction.

Open reduction is the treatment of choice for condylar fractures with displacement of the condyle into the middle cranial fossa, for compound fractures and where there is a foreign body in the joint.

Open reduction and rigid internal fixation should be contemplated for the edentulous or the mandible that compromise occlusal stability.

Open reduction may be the patient’s preference.

Matthias Schneider et al (2008)[16] suggested that fractures with a deviation of 10° to 45° or a shortening of the ascending ramus >2 mm should be treated with ORIF, irrespective of the level of the fracture.

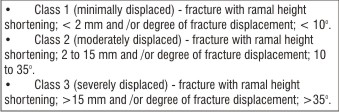

Amrish Bhagol et al. (2011)[17] proposed a new classification of subcondylar fractures of the mandible based on ramal height shortening and degree of fracture angulation

On radiographic analysis, they categorized the fractures into 3 classes. (Table 5).

| Table 5

|

According to this classification class 1 can be treated with closed method while open reduction is recommended in class 2 and class 3 patients.

Conclusion

The patients who could be benefitted from open reduction are a small subset of those with significant reduction of ramus height. A functional reduction of ramus height can be detected clinically through significant ipsilateral molar occlusal interference, through the inability to obtain maximum inter cuspation and through the radiographic finding of significant superior displacement of gonion.[3]

In the end based upon the suggestions by different surgeons we summarize & propose the following principles for open reduction of fractures of mandibular condyle:

1. Children before puberty to be treated conservatively with or without maxillo-mandibular fixation.

2. Open reduction is recommended in selected cases:

With displacement of the condyle into the middle cranial fossa and where there is a foreign body in the joint.

In severely dislocated fractures > 45o

Impossibility of obtaining adequate occlusion by closed reduction

In cases of loss of ramus height > 4mm

In edentulous patients with bi condylar fractures

In those with ‘medical problems’ where intermaxillary fixation is not recommended

References

1. Robert v. Walker. Condylar Fractures: Nonsurgical Management.J. Oral Maxillofac Surg 52:1185-1188, 1994.

2. Forouzanfar T, et al. Long-term results and complications after treatment of bilateral fractures of the mandibular condyle. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg (2013).

3. Leon A. Assael. Open Versus Closed Reduction of Adult Mandibular Condyle Fractures: An Alternative Interpretation of the Evidence. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 61:1333-1339, 2003.

4. Michael F. Zide and John N. Kent. Indications for Open Reduction of Mandibular Condyle Fractures.J Oral Maxillofac Surg 41:89-98, 1983

5. Michael F. Zide.Open reduction of mandibular condyle fractures. Clin Plast Surg 16:69, 1989

6. John N.Kent, Neary JP, Silvia C et al: Open reduction of mandibular condyle fractures. Oral Maxillofac Clin North Am 2:69, 1990

7. Giacomo De Riu, Ugo Gamba Marilena Anghinoni, Enrico Sesenna. A comparison of open and closed treatment of condylar fractures: a change in philosophy.Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2001; 30: 384–389.

8. Matthew B. Hall.Condylar Fractures: Surgical Management. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 52:1189-1192, 1994.

9. Nils Worsaae and Jens J. Thorn. Surgical VersusNonsurgical Treatment of Unilateral Dislocated Low Subcondylar A Clinical Study Fractures: of 52 Cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 52: 353-360. 1994.

10. Peter Banks. A pragmatic approach to condylar fractures. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg 27:244-246, 1998.

11. Ulrich Joos, Johannes Klelnheinz. Therapy of condylar neck fractures. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg 27:247-254, 1998.

12. Jelle Hovinga, Geert Boering et al. Long term results of nonsurgical results of condylar fractures in children. Int. J Oral Maxillojac. Surg. 28 : 429-440, 1999.

13. Undt G, Kermer C, Rasse M, et al: Transoral miniplate osteosynthesis of condylar neck fractures. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 88:534, 1999.

14. M. Todd Brandt and Richard H. Haug. Open Versus Closed Reduction of Adult Mandibular Condyle Fractures: A Review of the Literature Regarding the Evolution of Current Thoughts on Management. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 61:1324-1332, 2003

15. Nicholas Zachariades, Michael Mezitis et al. Fractures of the mandibular condyle: A review of 466 cases. Literature review, reflections on treatment and proposals.Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery 34: 421–432; 2006.

16. Matthias Schneider, Francois Erasmus et al.Open Reduction and Internal Fixation Versus Closed Treatment and Mandibulomaxillary Fixation of Fractures of the Mandibular Condylar Process: A Randomized, Prospective, Multicenter Study With Special Evaluation of Fracture Level. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 66:2537-2544, 2008.

17. Amrish Bhagol, Virendra Singh et al. Prospective Evaluation of a New Classification System for the Management of Mandibular Subcondylar Fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 69:1159-1165, 2011.

|