Introduction

Success of endodontic treatment depends on multiple factors, first and foremost being the complete removal of microorganism as well as pulp tissue from within the pulp space and for which complete information of internal morphology of radicular canals and possible variations is important.[1]

The permanent mandibular first molar is usually two-rooted, having a mesial and a distal root. The major variant in this tooth type is the presence of an additional third root; a supernumerary root which can be found lingually. The presence of this macrostructure, which was first mentioned in the literature by Carabelli,[2] is called Radix Entomolaris (RE). This variant of a third root in the permanent mandibular first molar has been described by various terms as well, such as distolingual root, additional or extra distolingual root and radix entomolaris.[3]

The permanent mandibular first molar is the earliest permanent posterior tooth to erupt, responsible for development of occlusion and other important physiologic functions like chewing. More often than not it has been observed to be in need of endodontic treatment.[4] Thus, it is of utmost importance that the clinician be familiar with variations in the roots and root canal anatomy of the mandibular first molar.

The present report describes successful root canal treatment of two patients having a third root in mandibular first and second molar teeth respectively.

Case 1

A 16-year-old male patient presented in the Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, Seema Dental College and Hospital, Rishikesh with extensive carious lesions in both right and left mandibular @257;rst molars, primary complaint being of spontaneous pain in both the teeth. On clinical examination the teeth were found to be sensitive to both hot and cold and tender on percussion. IOPA radiographs revealed deep carious lesions involving the pulp and also a third root which could be seen distinctly a little mesial to the distal root. Endodontic treatment were carried out for both teeth on separate occasions. (Fig 1 and Fig 2)

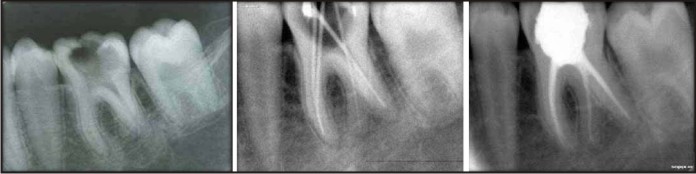

| Fig 1 : Case 1: Endodontic Treatment Of 36

|

| Fig 2 : Case 1: Endodontic Treatment Of 46

|

The tooth (36) was anaesthetised, and after removal of all caries the pulp chamber was opened using Endo access bur (Dentsply International). The access cavity trapezoidal in shape was modi@257;ed suitably a little more towards the distolingual in order to locate and open the ori@257;ce of the distolingually located RE. After scouting of the root canals orifices no. 15 K-flex file (Sybron Endo) was used to confirm the patency of the canals. Subsequent to confirmation of the patency flaring of the coronal thirds with Gates Glidden burs (Nos 3 and2) in a crown-down mode was done and radiographic length-determination was obtained.

The root canals were prepared with crown-down technique using K- flex files (Sybron Endo). As an adjunct to root canal preparation RC Prep (Premier, Norristown, PA, USA) was used and the canals were periodically irrigated using copius amounts of sodium hypochlorite solution (2.5%, Nova dental products Pvt Ltd). After completion of chemomechanical preparation, distilled water was used as a final irrigant. After drying the canals with suitable paper point, a cotton pellet dipped in Cresophene (Septodont) and squeeze dried was placed in the chamber and access cavity was sealed with CavitTM G (3M ESPE). The patient was recalled after 3 days for the dressing. The root canals were obturated on the third appointment with gutta-percha and AH Plus sealer (De Trey Dentsply, Konstanz, Germany) using the lateral condensation technique. The tooth was restored coronally with a high copper amalgam (SDI) restoration. Similar procedure was carried out for endodontic treatment of 46. An OPG was then taken after successful completion of the treatment. (Fig 3)

| Fig 3 : Case 1: Opg

|

Case 2

A 26 year old female patient reported to the Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, Seema Dental College and Hospital, Rishikesh with a chief complaint of extensive caries in lower right posterior tooth and food lodgment for the past few months. There was no complaint of apparent pain but, the patient gave a history of moderate to severe pain about 6 months ago which had than subsided after a course of antibiotics and analgesics.

Clinical examination revealed deep carious mandibular right second molar (47) which gave no response to electric pulp test. IOPA radiograph showed extensive carious lesion involving the pulp and also an additional root a little mesial to the distal root. Widening of periodontal ligament space was also observed on both the mesial and distal roots.

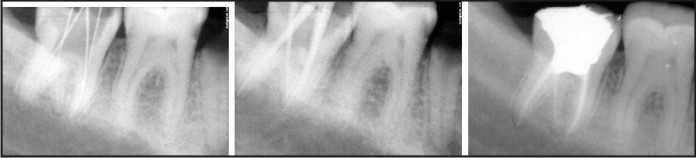

Subsequent to anaesthetizing the tooth and then removal of all caries an access cavity was prepared. On complete removal of the roof of the pulp chamber of the access cavity three canal ori@257;ces were initially identi@257;ed. On further exploration a second distal and more lingually located canal was found. Root canals were initially checked for patency using a no. 10 K-flex file (Sybron Endo). Canal lengths were checked with the AFA Apex@257;nder and con@257;rmed by means of a length determination radiograph taken from a mesial angulation. All canals were cleaned and shaped with ProTaper @257;les (Dentsply Maillefer) up to the F2-ProTaper and the irrigation protocol was followed. An interappointment calcium hydroxide dressing (Ultracal XS; Ultradent Products Inc., South Jordan, UT, USA) was placed in the canals.

The patient was recalled after two weeks for completion of the treatment and the tooth was found to be asymptomatic. The calcium hydroxide dressing was removed from the canals using minimum instrumentation and copius amount of irrigation. After drying, the canals were obturated with AH-Plus sealer and ProTaperTM gutta percha. The tooth was eventually restored coronally with high copper amalgam. (Fig 4)

| Fig 4 : Case 2: Endodontic Treatment Of 47

|

Discussion

The internal anatomy of tooth is not always similar. A great number of variations could occur in number of roots and their shape.

The expected root canal anatomy dictates the location of the initial entry of access; the size of the first file used, and contributes to a rationale approach for solving the problems that arise during therapy. Therefore, a thorough knowledge of the root canal anatomy from access to obturation is essential to give the highest possible chance for success.

Radix Entomolaris is a supernumerary distolingual root with various percentage of occurrences in different populations ranging from 3% of the African population[5] to more than 30% of the mongoloid population[6] while in Eurasian and Indian populations the frequency is less than 5%[3]. The etiology behind the formation of RE is still unclear. In dysmorphic supernumerary roots, its formation could be related to external factors during odontogenesis or presence of an atavistic gene or polygenetic system. According to Quackenbush[7], the extra root occurred unilaterally in approximately 40% of all cases and predominantly on the right side. This is also likely to be true, because we found one of these cases on the right side. Although some studies report a bilateral occurrence of the RE from 50 to 67%[8]

Based on the external root morphology and scouting of root canals, Radix Entomolaris could be classified in three groups. This classification is based on a classification proposed by Ribeiro & Consolaro.[9]

-

Type I refers to a straight root/root canal.

-

Type II refers to an initially curved entrance and the continuation as a straight root/root canals.

-

Type III refers to an initial curve in the coronal third of the root canal and a second buccally orientated curve starting from the middle to apical third.

The presence of an RE has clinical implications in endodontic treatment. An accurate diagnosis of these supernumerary roots can avoid complications or a ‘missed canal’ during root canal treatment. Because the (separate) RE is mostly situated in the same buccolingual plane as the distal root, a superimposition of both roots can appear on the preoperative radiograph, resulting in an inaccurate diagnosis. A thorough evaluation of the preoperative radiograph and interpretation of particular marks or characteristics, such as an unclear view or outline of the distal root contour or the root canal, can indicate the presence of a ‘hidden’ RE. To reveal the RE, a second radiograph should be taken from a more mesial or distal angle (30 degrees). This way an accurate diagnosis can be made in the majority of cases.

Identification of Radix entomolaris can be done by clinical inspection of the tooth crown and analysis of the cervical morphology of the roots by means of periodontal probing explorer, path finder, DG 16 probe and micro-opener, Champagne effect- bubbles produced by remaining pulp tissue in the canal, while using sodium hypochlorite in pulp chamber.

An extra lingual cusp or more prominent occlusal distal or distolingual lobe, in combination with a cervical prominence or convexity maybe indicative of Radix entomolaris; however an increased number of cusps is not necessarily related to an increased number of roots; however, an additional root is nearly always associated with an increased number of cusps, and with an increased number of root canals.[10]

The location of the orifice of the root canal of an RE has implications for the access cavity. The orifice of the RE is located disto - to mesiolingually from the main canal or canals in the distal root. An extension of the triangular opening cavity to the (disto) lingual results in a more rectangular or trapezoidal outline form. The operator should have no qualms about modification of the access opening whenever they suspect about the additional root and cutting down the distolingual portion of the tooth. Otherwise if the canal cannot be located and would be failed, so conservation of the tooth structure would be useless. If the RE canal entrance is not clearly visible after removal of the pulp chamber roof, a more thorough inspection of the pulp chamber floor and wall, especially in the distolingual region, is necessary. Visual aids such as a loupe, intra-oral camera or dental microscope can, in this respect, be useful.

Conclusion

The high frequency of a fourth canal in mandibular @257;rst molars makes it essential to anticipate and @257;nd all canals during molar root canal treatment. The possibility of an extra root should also be considered and looked for carefully. Proper angulation and interpretation of radiographs help to identify chamber and root anatomy.

References

1. Calberson FL, De Moor RJ, Deroose CA. The Radix Entomolaris and Paramolaris: Clinical Approach in Endodontics. J Endod 2007 Jan; 33(1):58-63.

2. Carabelli G. Systematisches Handbuch der Zahnheilkunde, 2nd ed. Vienna: Braumullerund Seidel, 1844, 114.

3. Tratman EK.Three–rooted lower molars in man and their racial distribution. Braz Dent J 1938; 64: 264-274.

4. Barker BCW, Parson KC, Mills PR, Williams GL. Anatomy of root canals. III. Permanent mandibular molars. Aust Dent J 1974; 19:403-413.

5. Sperber GH, Moreau JL. Study of the number of roots and canals in Senegalese @257; rst permanent mandibular molars. Int Endod J. 1998; 31:117-22.

6. Walker RT, Quackenbush LE. Three rooted lower @257;rst permanent molars in Hong Kong Chinase. Br. Dent J. 1985; 159:298-9.

7. Quackenbush LE. Mandibular molar with three distal root canals. Dent traumatol. 1986; 2: 48–9.

8. Steelman R. Incidence of an accessory distal root on mandibular first permanent molars in Hispanic children. J Dent Child 1986;53:122–3.

9. Ribeiro FC, Consolaro A. Importancia clinica y antropologica de la raiz distolingual en los molars inferiors permamentes. Endodoncia 1997; 15:7278 (English Abstr).

10. Carlsen O, Alexandersen V. Radix paramolaris in permanent mandibular molars: identification and morphology. Scand J Dent Res 1991; 99(3):189-95.

|