Introduction

Papillon Lefèvre syndrome was first described by two French physicians Papillon and Lefèvre in 1924[1]. It is also called as Juvenile (precocious) periodontosis with palmar plantar hyperkeratosis. Incidence of this syndrome is 1-4 persons per million and males & females are equally affected[2]. Parental consanguinity is seen in 20%-40% cases[3]. The common features of PLS include palmoplantar hyper keratosis associated with severe early onset periodontitis and premature loss of primary & permanent teeth. Gorlin et al stated that calcification of dura matter is the third component of the syndrome[4]. Additional symptoms & findings may include frequent pyogenic skin infection, nail dystrophy & hyperhidrosis. Patients with PLS are predisposed to develop pyogenic liver abscess due to impairment of the immune system.

Palmoplantar lesions usually have its onset during the time of tooth eruption between ages of six months to three years. Sharply demarcated erythematous keratotic plaques involve entire surface of palm and soles which may vary from mild psoriasiform scaly skin to hyperkeratosis. Other sites which may be affected include knees, elbows, eyelids, cheeks, labial commissures & dorsal of fingers etc. Hairs are usually normal but the nails may show transverse grooving and fissuring.

Dental involvement is typically evident immediately after tooth eruption and is accompanied by severe gingival inflammation. Development and eruption of deciduous teeth start normally but gingiva is bright red & bleeds easily even in absence of any local etiologic factor. It leads to exfoliation of all the primary teeth by age of 4-5 years[1]. After exfoliation, inflammation subsides and gingiva appears normal. As permanent teeth erupt, the same process of gingival inflammation and periodontitis is repeated, most of permanent teeth are lost by age of 15-17 years in the absence of dental treatment[5]. Teeth present ‘Floating in air’ image on dental radiography due to severe resorption of alveolar bone.

Here we report a case of PLS in 14 years old boy with classic clinical features.

Case Report

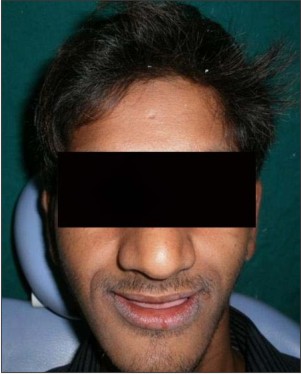

A 14 years old male patient presented to Department of Pedodontics & Preventive Dentistry, complaining of missing teeth and difficulty in eating due to mobile permanent teeth (Fig. 1). Past dental history revealed that his deciduous teeth had erupted normally but were lost gradually by age of 4-5 years. Similarly some of his permanent teeth were also lost prematurely after erupting normally. There was history of recurrent swelling of gums followed by loosening of permanent teeth. Thickening and scaling of palmoplantar skin was present since childhood. The skin lesions became worse during winters. History of consanguineous marriage was positive. Rest of family members including parents and six siblings were apparently normal.

| Fig 1: Pre-treatment extra-oral photograph

|

Clinical Examination

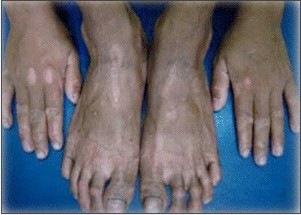

Cutaneous examination revealed well demarcated yellow keratotic plaques on his palms and soles (Fig. 2 & 3). The skin over dorsal surface of joints of hands & feet presented increased keratinization and affected skin was clearly demarcated from adjacent normal skin (Fig. 4). His nails and hair were normal.

| Fig 2: Palmar surface showing hyperkeratosis

|

| Fig 3: Plantar surface showing hyperkeratosis

|

| Fig 4: Dorsal surface of hands and feet showing keratotic plaques

|

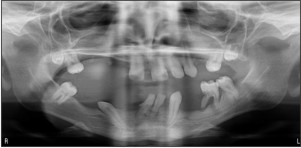

Intraoral examination revealed painful, swollen and bleeding gums along with halitosis (Fig. 5). The teeth present in oral cavity were 11, 16, 21, 22, 23, 27, 31, 33, 36, 37, 41, 43, and 47. Root stumps of 12 & 15 were also present. 41 & 36 showed grade III mobility. Pathological migration of the teeth present was visible (Fig. 6 & 7). The gingiva around teeth was inflamed and tender while it appeared normal in edentulous area. The orthopentograph revealed generalized alveolar bone loss giving the teeth “floating in air” appearance (Fig. 9). Class III profile was visible on lateral cephalogram (Fig. 8). Skull x-ray showed thickening of dura matter. Routine laboratory investigations were within normal limits.

| Fig 5: Intraoral photograph showing missing teeth and inflamed gingiva in relation to existing teeth

|

| Fig 6: Intraoral photograph showing missing teeth in mandibular arch

|

| Fig 7: Intraoral photograph showing root stumps and missing teeth in maxillary arch

|

| Fig 8: Cephalogram showing class III profile

|

| Fig 9: OPG showing “floating in air” appearance of the teeth

|

On basis of history and mentioned clinical findings, diagnosis of PLS was made.

Treatment

Extraction of root stump 12 and grade III mobile teeth 36 & 41 was done. Patient was put on antibiotics and mouth wash followed by complete oral prophylaxis. Oral hygiene maintainace instructions were given to patient. Distally tilted tooth 33 was up righted after completing the root canal treatment. Complete oral rehabilitation was done with transitional dentures in the maxillary & mandibular arch (Fig. 10). Consultation of dermatologist was taken for hyperkeratosis of palmar & plantar surfaces.

| Fig 10: Post treatment photograph of the patient with removable partial prosthesis

|

Discussion

A case of PLS is classified on basis of following three criterias – a) palmoplantar hyperkeratosis b) early loss of deciduous & permanent teeth c) autosomal recessive inheritance[6]. With both the parents as recessive carriers, there are 25% chances of producing offsprings with PLS[3].

Etiology of PLS is still unknown. Multiple factors are involved in causation of PLS. An impairment of neutrophil chemotaxis, phagocytosis & bactericidal activities, presence of actinobacillus actinomycetemocomitans (virulent gram negative anaerobic pathogen) in periodontal pockets, impaired immune mediated mechanisms like depression of helper/suppressor T cells ratio & elevation of serum Ig G are some of the important factors. And recently, PLS gene locus has been localized to chromosome 11q14-21 where mutation of cathepsin C gene occurs[2]. The cathepsin C gene encodes a cysteine-lysosomal protease also known as dipeptidyl-peptidase I. The cathepsin-C gene is expressed in epithelial regions commonly affected by PLS such as palms, soles, knees, and keratinized oral gingiva.

In our case report, the symptoms, clinical findings and past dental history resembles to the classical syndrome of PLS. Because of low socioeconomic status of the patient, genetic testing could not be performed. But the case reported was associated with consanguinity of parents. As parents were healthy and there was no family history of disease, autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance was suggested.

Although Hiam-munk syndrome and PLS share the cardinal features of palmoplantar keratoderma and pre-pubertal periodontitis as both come under the type IV palmoplantar ectodermal dysplasias. But the sufferers of HMS also exhibit arachnodactyly, acro-osteolysis and deformities of phalanges of hand[7].

Life threatening disorders like leukemia and neutropenias should be excluded because they also present with loosening of teeth along with extensive gingivitis, haemorrhage and ulceration[8].

Acrodynia also known as Feers’ syndrome, shows premature loss of deciduous and/or permanent teeth, is caused by mercury intoxication. But in this condition erythrocyanosis, muscle pain, insomnia, sweating and psychic disturbances are additional features. It presents in children between ages of six months and four years[9],[10].

In hypophosphatasia, the teeth, which are hypoplastic, are prematurely shed. There are increased amounts of phospho ethanolamine in the urine[9].

Some other disorders in which premature loss of primary and permanent teeth occur are Langerhans cell histiocytosis, Chediak-Higashi syndrome and Takahara’s syndrome[8].

Other conditions which are associated with palmoplantar keratosis but without periodontopathy are palmoplantar hyperkeratosis of Unna Thost, mal de Meleda, Howel-Evans syndrome, keratosis punctate and Greither’s syndrome[10],[11].

Recent studies have shown that PLS syndrome is manageable and permanent teeth can be saved. Various treatment modalities have been proposed for PLS like early extraction of primary teeth, construction of complete denture after removal of primary teeth, systemic and local antibiotic treatment and synthetic retinoids[3] & then adjustment of denture base to allow emergence of permanent dentition. Oral retinoids (aciretin, etretinate & isoretinoin) are main course of treatment for both keratoderma & periodontitis associated with PLS. If oral retinoids are given before eruption of permanent teeth at age of 5 years, normal dentition can be maintained[7]. Without treatment these patients could be rendered edentulous at very young ages which instills social phobia in these patients and they are unable to communicate with others. The use of implants could considerably improve future treatment options for oral rehabilitation[12].

Summary

This case is presented here because of importance of its early diagnosis and intervention by Pedodontists because most of times they are the first to come in contact with such patients and can help the patients to maintain their dental health.

References

1. Papillon MM, Lefèvre P. Two cases of symmetrical, familial (meloda’s malady) palmar and plantar keratosis of brother and sister; coexistence in two cases with serious dental changes (in French), Bullsoc Fr dermatol syphiligr 1924;31:82-7.

2. Angel TA, Hsu S, Kornbleuth SI, Kornbleuth J, Kramer EM. Papillon-Lefevre syndrome, a case report of four affected siblings. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002;46:S8-10.

3. T. C. Hart and L. Shapira, “Papillon-Lefevre syndrome,” Peri-odontology 2000, vol. 6, pp. 88-100, 1994.

4. Gorlin RJ, sedano H, Anderson VE. The syndrome of palmar-plantar hyperkeratosis and premature periodontal destruction of the teeth: A clinical and genetic analysis of the Papillon-Lefevre syndrome. J Pediatr 1964;65:895-908.

5. F. N. Hattab, M. A. Rawashdeh, O. M. Yassin, A. S. al-Momani, and M. M. al-Ubosi, “Papillon-Lefevre syndrome; a review of liteture and report of 4 cases,” Journal of Periodontology, vol. 66, no. 5, pp. 413-420, 1995.

6. Haneke E. The Papillon-Lefevre syndrome: keratosis palmoplantaris with periodontopathy. Human Genetics1979; 51:1-35.

7. Patel S, Davidson LE. Papillon-Lefevre syndrome: A report of two cases. Int J Paediatr Dent 2004;14:288-94.

8. Glenwright HD, Rock WP. Papillon-Lefevre syndrome. A discussion of aetiology and a case report. British Dental Journal 1990; 20:662-667.

9. Ashri NY. Early diagnosis and treatment options for the periodontal problems in Papillon-Lefevre syndrome: A literature review. J Int Acad Peridontol 2008;10:81-6.

10. Singla A, Sheikh S, Jindal SK, Brar R. Papillon-Lefevre syndrome: Bridge between Dermatologist and Dentist. J Clin Exp Dent 2010;2:e43-6.

11. Hattab FN, Anan WM. Papillon-Lefevre syndrome with albinism, a review of the literature and report of 2 brothers. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Patho Oral Radio Endod 2005;100:709-716

12. Patel SJ, Umarji RH. Papillon-Lefevre syndrome: A case report. J Indian Acad Oral Med Radiol 2004;16:306-10.

|