Introduction

Accessory cusps are common variations of tooth morphology that are occasionally seen. Clinically three of the most commonly reported variations of accessory cusps are the Carrabelli cusps of the molars (52% - 68%), Talon cusps of the incisors (1 -7.7 %) and Leong’s tubercle of the premolar (8 %).[1] The Carabelli cusp, a distinguishing morphological developmental anomaly is usually positioned on the mesiopalatal surface of the upper first permanent molars and rarely on the second or third permanent molars, or on the upper first primary molars.[2],[3] The nomenclature of this anatomical trait has been attributed to George Carabelli, who first described it in 1842 in a paper by Korenhof.[4],[5] It has also been variously referred to as the fifth lobe, supplemental cusp, mesiolingual elevation, accessory cusp, tuberculum anomalies, tuberculum Carabelli and tuberculum imparon.[5],[6] The feature that distinguishes cusp of Carabelli from dens evaginatus, which are also accessory cusps is the presence of pulp within which is in contradiction to carabelli cusp.[7],[8]

The etiology of the Carabelli cusp remains vague, and its origin is attributed to both genetic and exogenous factors. However, it is usually opined that the phenotypical appearance of the cusp is genetically determined, with data from studies on twins substantiating this hypothesis.[2],[5],[9] The Salazar-Ciudad and Jernvall model of tooth morphogenesis explains the development of tooth shape and manifestations of new cusps, based on a small number of developmental parameters. This theorem envisages covariation among morphological variables, such as tooth size, intercusp distances, and cusp size.[10] Mutual communications between oral epithelium and neural crest-derived mesenchyme influence the folding of internal enamel epithelium, which serves as an outline for crown structure.[11] The model believes that the pivotal point is the molecular signaling activity of enamel knots which direct the folding of the dental epithelium at the future spots of cusp tips.[10] These enamel knots are groups of nondividing cells, that act as signaling centers which are associated with the folding of internal enamel epithelium - which serves as an outline for crown structure.[11] With the distance from a preexisting enamel knot increasing there is an increased possibility of escaping the inhibition field surrounding the enamel knot, which may give rise to a new enamel knot, and thus a new cusp. This carabelli trait materializes from the palatal surface of the protocone (the mesiolingual cusp of upper molars) and succeeds the initiatation of the four major cusps of the molar. However, during occasional instances where it is as high as the other cusps, it commences simultaneously. Carabelli is more likely to be present and, if present, is more likely to be large in teeth with low intercusp distances relative to tooth size.[10] One study proposed that in individuals with the genotype for Carabelli trait expression, larger molar crowns are more likely to display Carabelli cusps in comparison to smaller molar crowns which are more likely to display reduced forms of expression.[10] Studies have also revealed that, on the whole there is no sexual preference in prevalence of this trait. [6],[12], Though generally bilateral, cuspal size and morphology discordance is noted.[6], [13]

Case Report

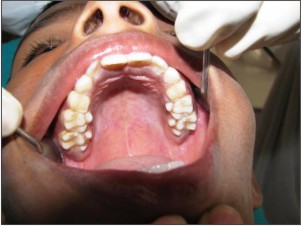

A 9 year boy reported for routine dental checkup. Intraoral examination incidentally revealed the presence of bilateral Synder’s type 5 cusp of carabelli on both the maxillary deciduous second molar and permanent first molar (Fig 1).

| Figure 1: Intraoral photograph showing bilateral Carabelli cusps

|

Intraoral periapical radiographs revealed well defined cusps with sound enamel margins, with no evidence of pulpal extension into the cuspal architecture. The necessity of maintaining good oral hygiene, with special emphasis on the carabelli regions and regular follow up has been impressed upon the patient, owing to the nature of the entity which can serve as foci of plaque retention and resultant caries development.

Discussion

Teeth have proven to be an extremely valuable paleontology material to grasp the evolution of mankind. One of the first traits to be recorded in such an exploration was Carabelli's trait, as early as in 1842.[5] A Carabelli cusp in the pit form has been discovered in Australopithecus, Neanderthal man and Dryopithecus rhenanus.[2],[5] Carabelli's trait on the maxillary molars has also been noted intermittently on some fossils of Paleolithic man. Consequently, there exists an suggestion that Carabelli’s cusp has evolved from a simple groove to its present form of a well-developed cusp. Notwithstanding these findings it generally opined that the cusp form of the Carabelli trait is a recent acquisition of man. These findings lend support to the belief that Carabelli trait is noteworthy in the evolution of man and, perhaps in different racial groups.[4],[5]

The trait can present as a shallow furrow or groove, a pit, a tubercule of varying size or even as a cusp with a free apex which challenges the hypocone (one of the molar’s four principal cusps) in size.[5],[10] Carabelli's trait is expressed as either on the lingual surface of the protocone of the primary maxillary second molar, or the permanent maxillary first molar.[5]

In 1944, Dietz found that the so-called Carabelli "tubercle" or "cusp" had a variety of expressions and identified 4 main categories viz. lobular, cuspoid, ridged, and pitted.[9]

Carabelli’s trait was graded by Snyder and coworkers into: [5]

0. no cusp and smooth – a completely smooth surface;

1. no cusp but small line – a surface having a furrow interrupting its continuity;

2. no cusp but pit – a surface having a pit interrupting its continuity;

3. cusp outline without apex – an eminence without a defining groove;

4. partial cusp without apex – a small cusp with a groove setting it off from the tooth surface; and

5. cusp with apex – a large cusp

Dahlberg’s scale for the determination of degree and expression of Carabelli cusps is as follows:[2]

0. No vertical ridges, pits, or other manifestations on the mesiolingual cusp

1. Small vertical ridge and groove

2. Small pit with minor grooves diverging from a depression

3. Double vertical ridges or slight and incomplete cusp outline

4. Y form: moderate grooves curving in opposite directions

5. Small tubercle

6. Broad cusp outline or moderate tubercle

7. Large tubercle with free apex in contact with lingual groove (height often approximates that of major cusps)

Meredith and Hixon classified it as: [13]

Category 1 There is a moderate to large lingual elevation separated from the mesiolingual cusp by a well-demarcated, archlike groove.

Category 2 There is a moderate to large lingual elevation separated from the mesiolingual cusp by a well-demarcated, partial groove.

Category 3 There is a slight elevation projecting from the lingual surface of the mesiolingual cusp.

Category 4 There is no definite protuberance from the lingual surface of the mesiolingual cusp.

Sousa, Carvalho & Pereira recognize the following degrees of the cusp:[3]

0. absent tubercle,

1. depression – for the surfaces that have a fovea which is associated or not to grooves,

2. mild – when it has a mild prominence and

3. prominent – when this prominence is more developed.

Prevalence of cusp of Carabelli varies amongst different racial populations. The cusp has been reported in 17.4 - 90% of white population, 37% of the Caucasoids but is a rare occurrence in Asians.[7],[14] Prevalence data for the primary dentition for all degrees of Carabelli’s trait indicate that it is more frequent in Caucasian children than in Mongoloid.[5] For the permanent dentition, Carabelli’s trait appears commonly amongest European populations, followed by African populations, and American Indians, with the lowest prevalence occurring in the other Mongoloid races.[5],[15] Yaacob opined that in the mongoloid race cusp of Carabelli is largely absent and if present, it is more often than not in a reduced form.[4],[14] In a study involving pediatric Saudi nationals the prevalence of the trait was 58.7% with similar prevalence in both males and females.[12] An investigation by Falomo on 2,604 Nigerians revealed prevalence rate of 17. 43%.[6] A recent study conducted in Franca involving 402 teeth in the age group of 4 to 13 years, found a prevalence rate of 69.52% in the second primary molars and in 52.09% of the first permanent molars with a predominance of depression type and rare occurrence of prominent cuspal type.[3]

Carabelli cusp is not known to interfere with occlusion, probably because they develop and attrite at the same rate as the other cusps. Presence of this additional extension of tooth structure may pose various dental problems such as caries originating in the pits or deep developmental grooves between the accessory cusp and crown, as these serve as potential stagnation areas. Hence these areas should be sealed with pit and fissure sealant. These cups may also pose problems in adapting the matrix band during restorative procedures.[1],[6]

Cusp of carabelli is a regularly noted yet often overlooked anatomical variant, with not much of a diagnostic or endodontic significance but a huge anthropological and forensic implication.

References

1. Nagarajan S, Sockalingam MP, Mahyuddin A. Bilateral accessory central cusp of 2nd deciduous molar: an unusual occurrence. Arch of Orofac Sci 2009; 4(1): 22-4.

2. Mavrodisz K, Rozsa N, Budai M, Soós A, Pap I, Tarjan I. Prevalence of accessory tooth cusps in a contemporary and ancestral Hungarian population. Eur J of Orthodontics 2007;29: 166–9.

3. Ferreira MA, Hespanhol LC, Capote TSO, Gongalves, MA & Campos JADB. Presence and morphology of the molar tubercle according to dentition, hemi-arch and sex. Int. J. Morphol. 2010; 28(1):121-5.

4. Carbonell VM. The tubercle of Carabelli in the Kish Dentition, Mesopotamia, 3000 B.C. J Dent Res1960; 39: 124-8.

5. King NM, Tsai JSJ, Wong HM. Morphological and numerical characteristics of the southern chinese dentitions. part II: traits in the permanent dentition. The Open Anthropol J 2010; 3: 71-84

6. Falomo OO. The cusp of Carabelli: frequency, distribution, size and clinical significance in Nigeria. West Afr J Med. 2002 Oct-Dec;21(4):322-4.

7. Levitan ME, Himel VT. Dens evaginatus: literature review, pathophysiology, and comprehensive treatment regimen. J Endod 2006;32:1–9

8. Jerome CE, Hanlon Jr RJ. Dental anatomical anomalies in Asians and Pacific islanders. CDA J 2007; 35(9): 631-6.

9. Kraus BS. Carabelli's anomaly of the maxillary molar teeth - observations on Mexicans and Papago Indians and an interpretation of the inheritance. Am J Hum Genet. 1951 December; 3(4): 348–355

10. Hunter JP, Guatelli-Steinberg D, Weston TC, Durner R, Betsinger TK (2010) Model of tooth morphogenesis predicts carabelli cusp expression, size, and symmetry in humans. PLoS ONE 5(7): e11844. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.00118 44

11. Kondo S, Townsend GC. Associations between carabelli trait and cusp areas in human permanent maxillary first molars. Am J Phys Anthropol 2006; 129:196–203.

12. Salako NO, Bello LL. Prevalence of the Carabelli trait in Saudi Arabian children. Odonto Stomatologie Tropical 1998; 21(84): 11-4.

13. Meredith HV, Hixon EH. Frequency, size, and bilateralism of Carabelli's tubercle. J Dent Res 1954; 33: 435- 440

14. Yaacob H, Narnbiar P, Naidu MDK. Racial characteristics of human teeth with special emphasis on the Mongoloid dentition. Malaysian J Pathol I996; 18(1): 1-7.

15. Katinka RN. Prevalence and treatment possibilities of numerical, morphological dental anomalies and malposition during childhood. University of Szeged; 2008. Available from: www.phd.szote.uszeged.hu /Klinikai_DI/.../ thesis_en_ Rozsa_Noemi.PDF

|