Introduction

Modern society has placed a strong emphasis on physical appearance. The desire to improve dentofacial esthetics has been found to be the primary motivation for patients seeking orthodontic care, regardless of structural or functional considerations.[1],[2],[3],[4]

Therefore, self-perception of their own dentofacial attractiveness is a key motivational factor for patients seeking orthodontic evaluation and is an important factor in their expectation of treatment outcome. However, this self-perception essentially is based on how individuals see themselves in the mirror, with frontal views of the face and smile typically representing their primary concerns.[1],[5]

Although orthodontic diagnosis is carried out in three dimensions (transverse, anteroposterior, and vertical), orthodontists place major treatment planning emphasis on the esthetics of the face in profile.[6],[7] Because most people cannot characterize their own profile,1 a difference does exist between orthodontic professionals and the public regarding perceptions of facial profile esthetics.[3],[8]

The aim of the current study, using a sample of subjects seeking or referred for orthodontic evaluation, was to determine whether exposure to pretreatment smile and profile photographs influenced individuals self-perception of dentofacial attractiveness and willingness to undergo treatment.

Materials & Methods

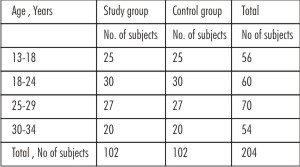

This questionnaire-based study included two groups of subjects: 102 subjects (46 females and 56 males; referred to as the Study Group) who were selected among individuals referred to the Department of Orthodontics within Rajasthan Dental College & Hospital, Jaipur (India), and 102 additional age- and sex-matched subjects (the Control Group). The study took place between 2010 and 2011. Given the difficulty involved in finding exact age matches, selection of controls was based on a range of ±6 months independent of the year of birth. The distribution of subjects’ ages is presented in Table 1

| Table 1 : Sample distribution by Age

|

All participants met the following inclusion criteria: (1) Rajasthan origin, (2) older than 13 years of age, and (3) seeking or referred for orthodontic evaluation. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) previous orthodontic treatment or plastic or orthognathic surgery, and (2) any systemic medical condition that might affect subjects’ physical or emotional growth, including psychiatric conditions.

Data Collection

Subjects’ responses regarding their perceived dentofacial attractiveness and willingness to undergo treatment were recorded using a specially designed questionnaire. The first section of the questionnaire focused on the demographic data of participants, such as age, gender, marital status, income level, and level of education. Subjects were asked whether they liked the appearance of their smiles (Question #1) and the appearance of their faces in profile (Question #2), using a 4-point scale with 1 as “very much,” 2 as “somewhat,” 3 as “a little bit,” and 4 as “not at all.” Finally, subjects were asked which treatment options they would seek to change the appearance of their smiles (Question #3) and their facial profiles (Question #4), using a 4-point scale with 1 as “None,” 2 as “Removable orthodontic appliance,” 3 as “Fixed orthodontic appliance,” and 4 as “Surgery.”

Photographs of frontal and profile views of the face, both at rest and while smiling, were taken of each participant using a Nikon Digital SLR Camera D70 under standard conditions. Several photos of each subject were produced, so that natural and unforced neutral facial expressions and smiles could be chosen and subsequently printed.

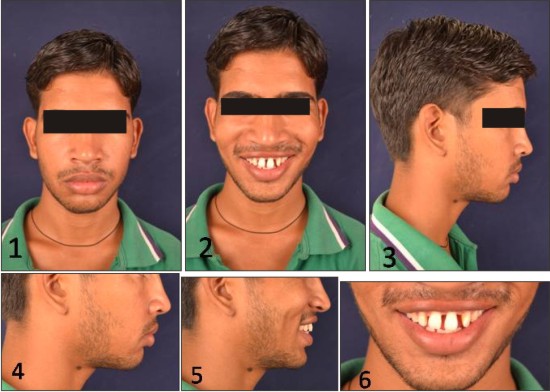

All subjects filled in the questionnaire twice, separated by an average interval of 15 days (T0, first completion; T1, second completion), and both questionnaires for a particular subject were identified by the same numeric code. During the period between T0 and T1, only subjects in the Study Group were given a printed copy of the photographs of themselves (Figure 1). They were instructed to show the photographs to relatives and friends for discussion.

| Figure 1 : Representative photograph used in this study

|

Statistical Analysis

Responses from the first and second completions of the questionnaires were coded. The differences between T0 and T1 were evaluated for each response and compared between groups using a chi-square test.

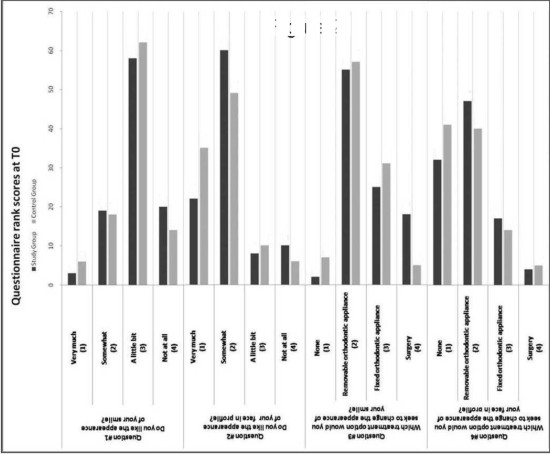

A logistic regression analysis was applied to adjust for all potential confounders (i.e., age, marital status, level of income, level of education,). The outcome was a negative change in subjects’ opinions between T0 and T1. (Figure 2,3)

| Figure 2 : Questionnaire ranks score at T0

|

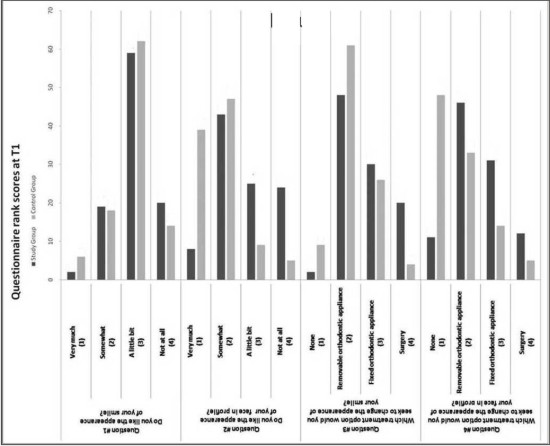

| Figure 3 : Questionnaire ranks score at T1

|

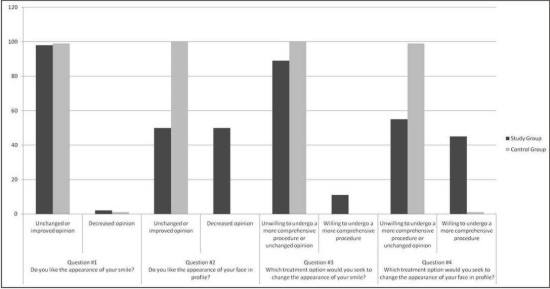

| Figure 4 : Unchanged And improved opinions

|

Responses to the Questionnaire

Questionnaire rank scores at T0 and at T1 are illustrated graphically in Figures 2 and 3, respectively, for both groups.

With respect to Questions #1 and #2, a positive value for the differences between ratings at T0 and at T1 was considered to be indicative of a decrease in patients’ opinions regarding the appearance of their smiles or facial profiles. A value of 0 indicated no change, and a negative value suggested an improved opinion. Because only a few improved opinions were found at T1, unchanged and improved opinions were grouped together (Figure 4).

With respect to Questions #3 and #4, a value of 0 for the difference between ratings measured at T0 and at T1 indicated no change in subjects’ opinions. A positive difference revealed that subjects were willing to undergo a more comprehensive procedure to change their appearance, and a negative score suggested that they were unwilling. Because only a few subjects were unwilling to undergo a more comprehensive procedure at T1, 0 values and negative scores were grouped together (Figure 4).

Comparison Between Groups

No differences were noted between groups with respect to participants’ opinions regarding the appearance of their smiles (χ2, 0.34;P > .05) between T0 and T1. However, a significant difference was found between groups with respect to subjects’ opinions regarding the appearance of their facial profiles (χ2, 86.30; P < .001) and the types of treatment they would seek to change their smiles (χ2, 15.89; P < .001) or facial profiles (χ2, 66.88; P < .001) between T0 and T1.

In the Study Group, 11% of subjects were willing to undergo more comprehensive therapies to change their smiles after exposure to photographs of themselves between T0 and T1. Moreover, 50% of patients in the Study Group had a more negative opinion regarding the esthetics of their facial profiles. Accordingly, 45% of subjects were willing to undergo more comprehensive therapies to change their profile appearance. No statistically significant difference was detected in the Control Group between questionnaire ratings at T0 and at T1.

Discussion:

Few previous questionnaire-based studies have investigated the self-perception of the attractiveness of the face, especially in the profile view, of individuals seeking orthodontic evaluation.[1] The ability of patients to recognize their profiles from among various silhouettes and photographs[1],[8] or to reproduce their own profiles had already been assessed.[9] Only one recent study investigated whether subjects requiring orthognathic surgery had seen their own facial profiles, and investigators assessed, using a questionnaire, whether subjects were happy with the appearance of their profiles.[10]

In the present study, a large sample of patients who were seeking or were referred for orthodontic evaluation was recruited. Exposure to the view of their pretreatment profiles and smile photographs, as well as discussions with relatives and friends, represented the “treatment variable” in the Study vs Control Group. Care was taken to ensure that the Control Group was matched for age and sex distribution—factors already found to influence subjective esthetic judgment and perception of orthodontic treatment need.[11] Because many adolescents are not fully aware of external motivating factors in the decision to undergo orthodontic treatment, only those individuals aged 18 years or older were included.[1],[11],[12]

No differences were found in questionnaire ratings between T0 and T1 for controls, thus implying that subjects not exposed to photographs of themselves did not change their self-perception of dentofacial attractiveness or their willingness to undergo treatment within the assessed period of 15 days. Similarly, no statistically significant difference was noted for either group between T0 and T1 with respect to scores for self-rated happiness with the appearance of their smiles. A statistically significant difference was noted between groups in terms of happiness with the appearance of their facial profiles and willingness to undergo treatment between T0 and T1. The main finding was that subjects exposed to photographs of themselves were significantly less happy with their facial profile appearance than were controls, with 50% of subjects in the Study Group negatively changing their opinions regarding the appearance of their own facial profiles at T1 (Figure 4). This observation is in accordance with previous findings that subjects who reported having seen their own faces in profile were less likely to be happy with their profiles.[1],[10]

In addition, previous studies have already concluded that patients are somewhat inaccurate in evaluating themselves, particularly regarding their own profiles.[9],[10],[13] Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that laypeople do not usually see themselves from a lateral view[14] and are thus unfamiliar with their own profiles unless exposed to photographs. Because orthodontic patients may become more conscious of their facial profiles owing to consultations that they receive at the beginning of treatment,[1],[11] in the present study care was taken to avoid any esthetic judgments made by the clinician, and, for the same reason, no explanations of the goals of the study were given.

At T1 in the Study Group, 11% of subjects were willing to undergo more comprehensive procedures to change the appearance of their smiles, and 45% were willing to undergo more comprehensive procedures to change the appearance of their facial profiles (Figure 4).

These results confirm that frontal perspectives of the face and the smile are more “familiar” to patients than the lateral view. Because orthodontists place major treatment planning emphasis on the anteroposterior dimension, a difference does exist between professionals' and patients' evaluations. At this point, a question arises as to whether self-perception of the esthetics of the face should be influenced by the orthodontist. It is the authors' opinion that such perception should be considerably guided by orthodontists, who are aware of the extent to which the therapeutic choice, combined with the effects of growth and aging (the so-called fourth dimension), would influence the overall dentofacial esthetic outcome. While discussing orthodontic diagnosis and treatment planning, patients' exposure to photographs proved to be a valuable tool in making the perceptions of patients match more closely those of orthodontists. This alignment of perceptions would result in more realistic motivations for and expectations of treatment on the part of patients.

Conclusion

Lay people are not generally aware of their facial profiles unless exposed to photographs.

Exposure to pretreatment facial photographs would reduce the discrepancy between patients' actual and perceived levels of facial attractiveness, thus making orthodontists' and patients' visual emphasis on dentofacial esthetics more similar to one another.

References

1. Tufekci, E. , A. Jahangiri , and S. J. Lindauer . Perception of profile among laypeople, dental students and orthodontic patients.Angle Orthod 2008. 78:983–987.

2. Cunningham, S. J. , N. P. Hunt , and C. Feinmann . Psychological aspects of orthognathic surgery: a review of the literature. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg 1995. 10:159–172.

3. Soh, J. , M. T. Chew , and Y. H. Chan . Perceptions of dental esthetics of Asian orthodontists and laypersons. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2006. 130:170–176.

4. Schlosser, J. B. , C. B. Preston , and J. Lampasso . The effects of computer-aided anteroposterior maxillary incisor movement on ratings of facial attractiveness. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2005. 127:17–24.

5. Shafiee, R. , E. L. Korn , H. Pearson , R. L. Boyd , and S. Baumrind . Evaluation of facial attractiveness from end-of-treatment facial photographs. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2008. 133:500–508.

6. Soh, J. , M. T. Chew , and H. B. Wong . A comparative assessment of the perception of Chinese facial profile esthetics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2005. 127:692–699.

7. Siqueira, D. F. , M. V. Sousa , P. E. Carvalho , and K. M. Valle-Corotti . The importance of the facial profile in orthodontic diagnosis and treatment planning: a patient report. World J Orthod 2009. 10:361–370.

8. Foster, E. J. . Profile preferences among diversified groups. Angle Orthod 1973. 43:34–40.

9. Hershon, L. E. and D. B. Giddon . Determinants of facial profile self-perception. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1980. 78:279–295.

10. Johnston, C. , O. Hunt , D. Burden , M. Stevenson , and P. Hepper . Self-perception of dentofacial attractiveness among patients requiring orthognathic surgery. Angle Orthod 2010. 80:361–366.

11. Wedrychowska-Szulc, B. and M. Syryńska . Patient and parent motivation for orthodontic treatment—a questionnaire study. Eur J Orthod 2010. 32:447–452.

12. Trulsson, U. , M. Strandmark , B. Mohlin , and U. Berggren . A qualitative study of teenagers' decision to undergo orthodontic treatment with fixed appliance. J Orthod 2002. 29:197–204.

13. Pitt, E. J. and K. Korabik . The relationship between self-concept and profile self-perception. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop1977. 72:459–460.

14. Soh, J. , M. T. Chew , and H. B. Wong . An Asian community's perspective on facial profile attractiveness. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2007. 35:18–24.

|