Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a group of metabolic diseases characterized by hyperglycemia resulting from defects in insulin secretion, insulin action, or both.1,2 The chronic hyperglycemia of diabetes is associated with a wide range of complications like diabetic retinopathy, atherosclerotic cerebrovascular, cardiovascular and peripheral vascular diseases, peripheral neuropathy, progressive renal dysfunction, delayed wound healing and periodontitis 3,4 .

Periodontal disease is considered to be the sixth complication of diabetes5.The interrelationship between diabetes mellitus and periodontitis has been studied for many years6. Diabetes and Periodontitis seem to interact in a bidirectional manner. Both these conditions can produce disability, and clinicians have long assumed that these diseases are biologically linked. The presumed link between diabetes mellitus and periodontitis is considered to stem from an increased susceptibility of people with diabetes to many types of infections, though this hypothesis has been questioned7. The diabetic state impairs the gingival fibroblast synthesis of collagen and glycosaminoglycan, enhances crevicular fluid collagenolytic activity, results in the loss of periodontal fibres, loss of the alveolar supporting bone, loosening and finally exfoliation of the teeth. One plausible biologic mechanism why diabetics have more severe periodontal disease is that glucose-mediated advanced glycation end products (AGE) accumulation would affect migration and phagocytic activity of mononuclear and polymorphonuclear phagocytic cells, resulting in the establishment of a more pathogenic subgingival flora. The maturation and gradual transformation of this subgingival microflora into an essentially Gram-negative flora will in turn constitute, via the ulcerated pocket epithelium, a chronic source of systemic challenge. This in turn triggers both an infection mediated pathway of cytokine upregulation, especially with secretion of TNF-a and IL-1, and a state of insulin resistance, affecting glucose-utilizing pathways. Excessive local secretion of TNF-a and IL-1 also mediates destruction of connective tissue and alveolar bone evident in periodontal disease.8 Nishimura et al (1998) have reported that high glucose levels decrease migration of periodontal ligament cells which compromises wound healing in periodontitis9.

From the epidemiological data regarding diabetes mellitus coupled with the possible close interrelationship between diabetes and periodontitis, it can be assumed that the dental practitioner and especially the periodontist are extremely likely to encounter an increasing number of undiagnosed diabetes patients with periodontitis and the clinicians who perform periodontal therapy must be especially aware and knowledgeable regarding the disease. Recent evidence indicates that diabetic complications such as retinopathy, cardiovascular disease and neuropathy may begin several years before the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus is established. The early diagnosis of diabetes, therefore, might help to prevent its long-term complications that are responsible for the high morbidity and mortality of these patients. Conversely, there is increasing evidence in controlled studies to indicate that severe oral infections of any type, including generalized periodontitis, may increase insulin resistance and possibly interfere with metabolic control of diabetes mellitus.6 So It has been suggested that prevention and management of periodontitis may be important to the successful management of NIDDM and that physicians treating patients with NIDDM should be alert to the signs of severe periodontitis 7. But it has been seen that the patients are often reluctant to seek medical evaluation and are resentful that the dentist would require medical consultation as a condition for receiving dental treatment. In such cases it is preferable for the dentist to perform screening blood glucose tests before starting the treatment.

For over 100 years, various methods have been used to measure glucose level in biological fluids, but the search for more specific, sensitive and simple method continues. Since centuries, the clinicians are sending venous blood, or urine samples for determining glucose levels to clinical biochemistry laboratories. But these days portable glucose monitors are in use both as a bed side testing of glucose by nurses in a hospital and for home testing conducted by patients under living conditions. These portable glucose monitors can be used for the estimation of blood glucose in dental set up also. As we know, the periodontal disease itself is associated with gingival bleeding and if the patient is diabetic, gingival bleeding is more severe. Bleeding from the gingival tissues is found to be further pronounced if the diabetic patient's condition is poorly controlled or is in association with undiagnosed diabetes10. Thus ample extravasated blood is produced during routine diagnostic procedures. Probing during a periodontal examination is more familiar to the practitioner and less traumatic than a finger-puncture with a sharp lancet. This blood oozing during routine periodontal examination can be the source for the estimation of blood glucose.

Therefore the aim of this study was to compare patient’s gingival crevicular blood glucose level (CrBGL) and finger puncture capillary blood glucose (CBGL) measurements using a self monitor so as to determine whether blood oozing from gingival tissues during routine periodontal examination can be used for determining glucose levels.

Materials And Method:

A total of 50 patients (22 male and 28 female; age range 24 to 70 years) visitng the Department of Periodontology and Oral Implantology, of Guru Nanak Dev Dental College and Research Institute, Sunam with moderate to severe periodontitis were screened and included in the study. Patients were examined and periodontal status was recorded with William’s graduated probe. Patients were classified according to AAP (American Academy of Periodontology) as moderate ( periodontal pocket depth 3-5 mm.) and severe ( periodontal pocket depth > 6mm.). On the basis of history and medical records, 25 known diabetic (test group) and 25 non-diabetic patients (control group) were randomly selected.

Patients with any of the following conditions were excluded from the study: requirement for antibiotic premedication; any disorder that is accompanied by an abnormally low or high hematocrit, e.g. polycythemia vera, anemia, dialysis; intake of substances that interfere with the coagulation system, e.g., coumarin derivatives, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, heparin; actual severe cardiovascular, hepatic, immunologic, renal, hematological, or other organ disorders.

The ethical approval was obtained from the college ethical committee and permission was taken from the Principal of the College and a written informed consent was obtained from all the willing participants.

Method

Bleeding gingival sites were determined. A site with more profuse bleeding was chosen for gingival crevicular blood. Maxillary anterior teeth were selected for taking samples and the sites were air dried to prevent contamination with saliva. Prior to probing, all the subjects were made to rinse with chlorhexidine gluconate 0.2% in order to minimize microbial load in the oral cavity. After that periodontal examination was done using Williams periodontal probe and the blood oozing from gingival tissues following periodontal pocket probing was collected with the strip of a glucometer (Optium Xceed by Medisense) and then reading was taken. Sites with suppuration were excluded from the study.

Following the crevicular blood another blood sample was obtained from one of the patient's finger. The soft surface of the finger tip was wiped with alcohol and the alcohol was allowed to evaporate. Sampling was carried out using an auto-lancet device to puncture the skin, and the blood drop was then collected by the strip of glucometer device for analysis and again the reading was taken according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical Analysis

The data was analyzed using SPSS version 13 software (SPSS Inc., USA). Descriptive statistics were obtained, means and standard deviation were calculated for comparing blood samples. The student’s t-test was used as test of significance for statistical evaluation of means. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was applied between CBGL and CrBGL. Statistical significance for all tests was accepted at p < 0.05.

Results

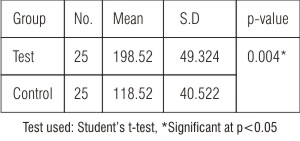

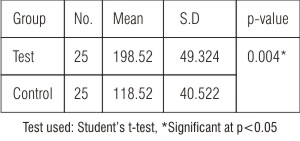

A total of 50 patients with equal number of diabetic (25) and non diabetic (25) were included in the study. The capillary blood glucose (CBGL) levels showed significant difference between test and control groups (p<0.05)  | Table: 1 Comparison of CBGL among test and control groups

|

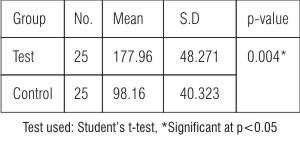

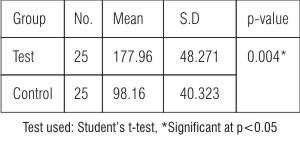

and similarly significant difference was found between test and control groups in gingival crevicular blood glucose levels (CrBGL) (p<0.05)  | Table: 2 Comparison of CrBGL among test and control groups

|

.

| Table: 1 Comparison of CBGL among test and control groups

|

| Table: 2 Comparison of CrBGL among test and control groups

|

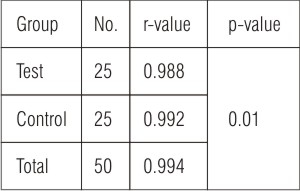

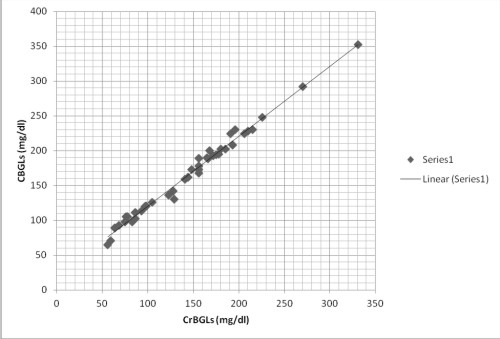

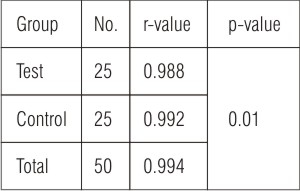

Correlation between fingerstrip capillary blood glucose (CBGL) and gingival crevicular blood glucose levels (CrBGL) (Fig 1)

Correlation between CBGL and CrBGL in the total sample were analyzed with "Pearson correlation coefficient" using the SPSS version 13 (statistical and data analysis). Highly significant correlation (r = 0.994) was found between CBGL and CrBGL in both test and control samples as (r = 0.988) and (r = 0.992) respectively at p<0.05  | Table: 3 Relationship Between Finger Strip Capillary And Gingival Crevicular Blood Glucose Levels

|

.

| Fig - 1 Correlation between CrBGLs and CBGLs among total subjects

|

| Table: 3 Relationship Between Finger Strip Capillary And Gingival Crevicular Blood Glucose Levels

|

Also while screening, four patients who were previously unaware were diagnosed with diabetes mellitus.

Discussion

The American Diabetes Association recommends that screening for diabetes should start at age 45 years and be repeated every 3 years in persons without risk factors, and earlier and more often in those with risk factors for diabetes. Moreover, testing at younger age or more frequently should be carried out in individuals who are (a) obese, (b) have a 1st-degree relative with diabetes, (c) are members of a high-risk ethnic population, (d) have delivered a baby weighing 4.05 kg or have been diagnosed with gestational diabetes mellitus, e) are hypertensive (>140/90), (f) have an HDL cholesterol level <35 mg/ dl and/or a triglyceride level >250 mg/ dl, (g) had on previous testing an impaired glucose tolerance or an impaired fasting glucose3. According to Collin HL et al (1998) advanced Periodontitis seems to be associated with the impairment of the metabolic control in patients with NIDDM and a regular periodontal surveillance is therefore necessary.11

Considerable effort has been made in the past few years for the development of painless and non-invasive methods to measure blood glucose. However, until now, none are in routine practice. There has been a recent effort to develop an accurate, safe, non-invasive means of evaluating the blood glucose level. Periodontal inflammation with or without the complicating factor of diabetes mellitus is known to produce ample extravasated blood during diagnostic procedures10, no extra procedure like finger puncture is necessary to obtain blood for glucose analysis. Mealey BL (1998) suggested that the diabetic patients may be encouraged to bring their glucometers to dental appointments so that blood glucose can be immediately assessed when needed12. Using the method described in this study, the periodontist can rapidly measure blood glucose many times using the gingival crevicular blood. It is necessary as resolution of periodontal inflammation in patients suffering from diabetes mellitus is successful only if blood glucose levels are controlled besides the removal of bacterial etiology. Consultation with the diabetic patient's physician routinely yields the result of a single blood glucose test. Since periodontal disease requires long-term treatment that often continues for years, a single blood glucose test will not be sufficient for periodontal management13. So the multiple measurements of a diabetic patient's blood glucose levels allow the periodontist to better assess the patient's diabetic control as the treatment progresses. Moreover, routine probing during a periodontal examination is less traumatic than a finger-puncture with a sharp lancet.

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the gingival crevicular blood glucose in order to reach a fast, safe, noninvasive, and convenient method to assess the diabetic status via periodontal examination. According to our findings, there is a highly significant correlation (r = 0.994, p<0.05) between finger stick capillary and gingival crevicular blood glucose levels between both test and control groups. This study is also supported by previous other studies13-15. Parker et al.13 reported a high degree of correlation between sulcular and capillary blood glucose,(r=0.8) which was consistent with the present study (r=0.99). Beiker et al.14 also reported a high degree of correlation in a study using a glucometer device to compare capillary and sulcular blood glucose levels (r=0.98). This is a much stronger relationship than reported by Tsutsui et al (r =0.782)16. In a study by Sarlati F et al (2010) the analysis of agreement failed to prove agreement between paired methods. But in diabetics this method revealed sufficient agreement. So they concluded that gingival crevicular blood can be used for testing blood glucose level during periodontal examination in diabetic periodontal patients but not in non-diabetics17. During screening of the patients, four patients who were previously unaware of being diabetic were diagnosed with diabetes. The incidence rate of Diabetes mellitus is on the rise. Hence if the dentists also participate in the routine screening of the patients for the diagnosis of the DM, it will be extremely beneficial. Testing crevicular blood glucose level with the self monitoring device is sensitive, since it can provide results with minimal of blood within a few seconds.

From the above discussion, we can say that gingival crevicular blood from probing may be an excellent source of blood for glucometric analysis using the technology of portable glucose monitors. Subjects can reliably be screened for diabetes by measuring glucose levels in gingival crevicular blood, since probing and sample collection takes a very little time and there is no discomfort to the patient. Thus, a dental clinician can use this crevicular blood to test for glucose levels instead of puncturing the patient’s finger tip to obtain a blood sample and can make a referral to a physician for further evaluation for diabetes when warranted.

Conclusion

Within the limits of this study, it can be concluded that there is a high correlation between gingival crevicular blood glucose levels and capillary blood glucose levels among diabetic and healthy subjects. Thus the gingival crevicular blood collected during diagnostic periodontal examination may be an excellent source of blood for glucometric analysis. In addition, the technique described is safe, easy to perform, and comfortable for the patient and might therefore help to increase the frequency of diabetes screening in dental set up.

References:

1. Newman M, Takei H, Kelokvld N, Caranza F: (Book) Clinical Periodontology. 10th Ed. 2006; Chap 15:313-315.

2. Rose L, Genco R, Mealey B, Cohen W: (Book) Periodontal medicine. 1st Ed. BC Decker Inc. 2000; Chap 8:129-36.

3. Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus (Report) 1997 Diabetes Care 20; 1183–1197.

4. Greenberg GM: Burkets oral medicine diagnosis and treatment. 10th Ed. BC Decker Inc. 2003; Chap 21:564-69.

5. Löe H : Periodontal disease: The sixth complication of diabetes mellitus, Diabetes care 16:329,1993.

6. Rees TD: Periodontal management of the patients with diabetes mellitus. Periodontology 2000; 23: 63–72

7. Taylor GW,Burt BA, Becker MP, Genco R, Shlossman M, Knowler W, Petit D : Severe periodontitis and risk factor for poor glycemic control in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Periodontol1996; 67:1085-93.

8. Grossi SG and Genco RJ: Periodontal disease and diabetes mellitus: a two-way relationship. Ann Periodontol 1998; 23: 51–61.

9. Nishimura F, Takahashi K, Kurihara M, Takashiba S, Murayam Y: Periodontal disease as a complication of diabetes mellitus. Ann Periodontol 1998; 3:20-9.

10. Ervasti T, Knuuttila M, Pohjamo L, Haukipuro K: Relation between control of diabetes and gingival bleeding. J Periodontol 1985; 56:154–157.

11. Collin H L, Uusitupa M, Niskanen L, Kontturi-Narhi V, Markanken H, Koivisto AM and Meurman JH: Periodontal findings in elderly patients with non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. J. Periodontol 1998; 69: 962–966.

12. Mealey BL; Periodontal implications in Medically Compromised Patients Ann Periodontol 1996; 1 :256-321

13. Parker RC, Rapley JW, Isley W, Spencer P, Killoy WJ: Gingival crevicular blood for assessment of blood glucose in diabetic patients. J Periodontol 1993 ;64:666–672.

14. Beikler T, Kuczek A, Petersilka G, Flemmig TF : In-Dental-Office screening for diabetes mellitus using gingival crevicular blood. J Clin Periodontol 2002; 29:216-218.

15. Ardakani MRT, Moeintaghavi A, Haerian A, Ardakani MA, Hashemzadeh M: Correlation between Levels of Sulcular and Capillary Blood Glucose. J Contemp Dent Pract 2009 March; (10)2:10-17.

16. Tsusui P, Rich SK, Schonfeld SE: Reliability of intraoral blood for diabetes screening. J Oral Med 1985; 40:62-66.

17. Sarlati F, Pakmehr E, Khoshru K, Akhondi N: Gingival crevicular blood for assessment of blood glucose levels. J. Perio. Implant Dent. 2010;2(1):17-24. |